200 years ago this June, The Weights and Measures Act 1824 was passed in the United Kingdom. Its message was clear: ‘there shall be but one Measure and one Weight throughout the Realm’.

This legislation introduced the Imperial system of measurement that we still use in some circumstances today, whether rating the fuel efficiency of cars in miles per gallon, or weighing ourselves in stone and pounds. It’s the reason that when you order a pint you should get exactly 568.261 millilitres of your chosen tipple. But how much difference did the act really make? And what does its purpose and timing tell us about ordinary people’s knowledge of weighing and measuring?

A long history

Weights and measures in the British Isles, as elsewhere, have a mind-bogglingly long and complex history that can be traced back thousands of years. Many ancient measures were based on body parts. A hand (still used for measuring horses today) was the width of the measurer’s fingers and thumb, a cubit the length from the elbow to fingertips. A foot was, well, a foot. Other measures were defined by certain actions. A Roman mile (mille passus) was 1000 paces. The acre was traditionally defined as the amount of land that could be ploughed in a day.

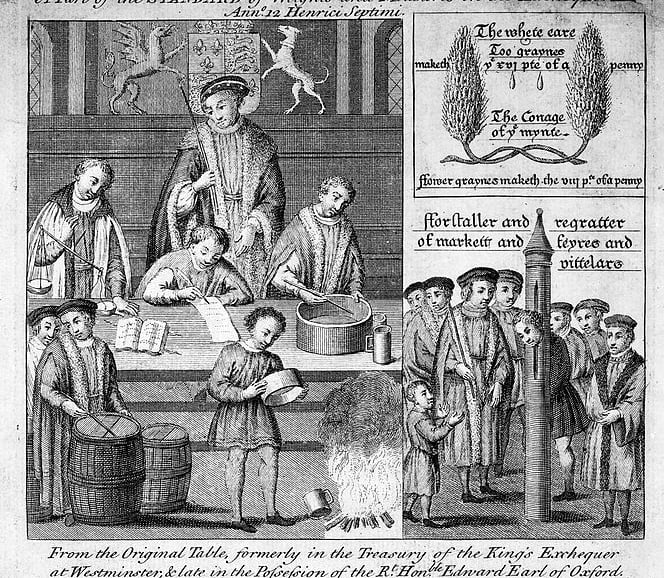

In many cases, the modern units we have inherited are only a little different to these qualitative measures, but over time the need for standardisation has seen weights and measures fixed to mathematically precise quantities. Since the Middle Ages, periodic appraisals of weights and measures known as assizes attempted to impose some degree of standardisation as units continually evolved alongside trading practices. In England, the ‘Exchequer Standards’, introduced in 1588, provided some uniformity to weights, but units such as the yard remained subject to reappraisal. In Scotland, an assize of 1618 sought to impose a single standard of weight for all goods. Following the union of Scotland and England into the United Kingdom in 1707, standard English weights were sent to be used in Scotland. In both the physical manifestation of weighing and measuring objects, and the regulation of trade that they enforced, weights and measures have long been sources of political and symbolic power.

Confusion beyond measure

Despite attempts to draw weights and measures into line, a wide variety of standards persisted from one town to the next and between Scotland and England. At the turn of the nineteenth century, the system in place – if it can be called a system – reflected centuries of evolution with endless local variation. On the surface, it was chaos!

Each market town retained its own standard weights and measures defined by the size of physical objects, so two units of the same name could constitute different amounts. For example, a bushel (a common English unit for measuring produce) might be a different quantity in one town compared to its neighbour, because the size of the ‘bushel’ itself (a bucket-like container) was different. As a volumetric measure, the precise quantity further depended on how tightly the container was packed, and whether the contents were ‘heaped’. In turn, the density of different substances varied according to the size of grain, the time of year they were harvested and even the temperature.

Another layer of complexity was that different goods required different measures. Cloth, for example, was typically measured not by inches and yards but by the ell, a derivation of the old cubit. Even more confusingly, units of the same name varied by the goods in question, hence the volume of a gallon differed depending on whether ale or wine was being measured. The ‘hundredweight’ was a misnomer: a ‘hundred’ of tin or copper was 112 lbs; ‘hundreds’ of fish were often 120 or 124 lbs.

It is easy to assume that these factors would have caused no end of difficulty, but we should not overstate the extent of the mayhem. The fact that these complex systems remained in place for so long demonstrates that they were generally fit for purpose. The ability to work with them, and to convert between different systems when necessary, must have been widespread skills.

Still, it was no wonder that discrepancies arose frequently. In the legal and administrative records of towns up and down the British Isles, it is common to find cases of shopkeepers and tradespeople reprimanded for possessing incorrect measures. In some cases, the accused would protest ignorance, claiming they weren’t aware that their measures were false. For example, in 1770 a woman known as widow Greenfield from Dunbar, East Lothian, was found selling grain with false weights, admitting that the ‘scale into which her meal was put to be weighed was about two ounces & a half heavier than the opposite scale’, but that ‘she was entirely ignorant... untill the Committee discovered it’. Such claims could of course have been a ploy to avoid punishment, but with such dizzying diversity of unitary standards, who could blame anyone for getting it wrong?

The reform campaign

By the turn of the nineteenth century, the pressure for reform was growing. In 1817 one reformer estimated that there were 230 distinct provincial standards in England and seventy in Scotland. The wording of the 1824 act reflected these anxieties:

In reality, however, the old customary weights were slow to disappear. It took two years for every market town to be supplied with new precision-made brass standard weights. The 1824 act also made provision for pre-existing customary weights to remain in use if the imperial conversion was properly understood. In Scotland, distinct measures pre-dating the British standards were still in occasional use at the end of the nineteenth century, including the ‘trone’ weight, the outlawing of which had been mandated since 1618, but never fully implemented.

The fact that standardisation could not be achieved overnight shows how deeply entrenched existing units of measurement were in the minds of the population at large. Though the brief story presented in this article represents a simplification of the complex history of weights and measures, it is always worth bearing in mind that behind the official legislation, political campaigns and scientific practices of measurement, the use of weights and measures has been a vital part of the knowledge possessed by ordinary people for a very long time. The great complexity and variety of pre-modern measurement systems reminds us that people in the past possessed the significant mental dexterity required to work with them. In today’s world of quantitative precision and ubiquitous technology to facilitate it, such cognitive capacities have largely fallen by the wayside.

Sources

East Lothian Council Archives, DUN/7/2/3/81, Greenfield et al. v Procurator Fiscal (1770).

R. D. Connor, The Weights and Measures of England (London, 1987).

R. D. Conner and A. D. C. Simpson, Weights and Measures in Scotland: A European Perspective (East Linton, 2004).

John Swinton, A Proposal for the Uniformity of Weights and Measures in Scotland (Edinburgh, 1779), p. 4.

Keith Thomas, ‘Numeracy in Early Modern England: The Prothero Lecture’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 37 (1987), p. 123.

People who use... measures differing both in size and name, speak as it were different languages; and it is not enough to make a law appointing all persons to speak the same language… without also making some provision for teaching them to do so.

When the 1824 act was finally passed, it repealed all previous legislation, and introduced new standards across the board for weight, volume, length and area. It also brought Scottish and English measures into line to a greater extent than ever before and, as the name suggests, implemented a standardised system across the British Empire.

…different Weights and Measures, some larger, and some less, are still in use in various Places throughout the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the true Measure of the present Standards is not verily known, which is the Cause of great Confusion and of manifest Frauds.

A sustained campaign to standardise weights and measures began in Britain as early as the mid-eighteenth century amidst the development of metrology as a scientific field. The benefits of having universal standards across Britain were obvious, but one question remained: how would the general population respond to the threat of losing the old customary measures that were so deeply ingrained in the habits of local communities?

As one ardent campaigner for standardisation, the lawyer John Swinton, warned,