Abracadabra, amor-oo-na-na

Abracadabra, morta-oo-ga-ga

Abracadabra, abra-oo-na-na

In her tongue she said, ‘Death or love tonight’

So goes the chorus in the latest Lady Gaga smash-hit, ‘Abracadabra’.

With a healthy 300 million+ plays on Spotify at the time of writing, on top of the 100 million views of the track’s limb-flailing frenzy of a music video, the song is just the latest in a succession of pop-cultural landmarks evoking the magic of ‘abracadabra’.

Those of a certain age might remember Steve Miller Band’s 1982 hit of the same name (the one that goes “Abra-abracadabra, I wanna reach out and grab ya”), or the Eminem song in which it’s sampled.

In fact, a deep dive through history shows us that this magical term has been a familiar resident in the lexicons of people across the world for millennia.

Abracadabra through the ages

As the historian Tom Metcalfe explains, there are a variety of theories as to the word’s etymology, but likely candidates are Hebrew or Aramaic phrases (אברא כדברא) denoting the creation of things, especially through speech. Whatever the origins, the term has long been associated with magic and conjuring, particularly in relation to preventing and curing disease.

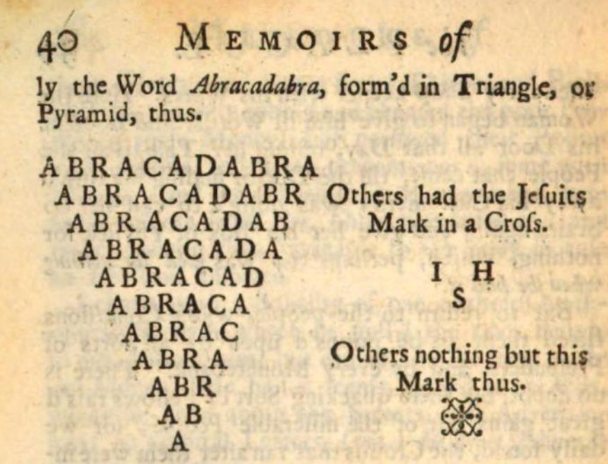

One particularly common manifestation of the term has been to write it in a triangular shape with one letter less in each line, like so:

ABRACADABRA

ABRACADABR

ABRACADAB

ABRACADA

ABRACAD

ABRACA

ABRAC

ABRA

ABR

AB

A

This was the form it took in one thirteenth-century manuscript copy of a third-century medical text by the Roman author Quintus Serenus Sammonicus, who suggested it could be used as a malaria cure. Often the triangular spell would be written on parchment then folded and worn around the neck as an amulet. A mysticism surrounding the written word in an era before mass literacy probably added to its perceived power, as was the case for some medieval Catholic prayers which were also worn in amulet form.

These practices were also common in Jewish in Islamic societies. For example, the Talmud mentioned a demon by the name of Shavriri (שברירי) who could be deterred by writing its name and removing letters just like with abracadabra. Islamic occultists like the thirteenth-century writer Ahmad Al-Buni also used combinations of verses and letters to invoke or protect against all manner of supernatural beings in his book Shams al-ma’arif (شمس المعارف).

Magic, belief and doubt

Triangular abracadabras were among the ‘charms, philtres, exorcisms, amulets’ that Daniel Defoe recalled helpless would-be victims wearing during London’s Great Plague of 1665. Defoe wrote dismissively of these ‘superstitious’ practices, and whether or not this observation was actually true was another matter. But it says much about the popular recognition of abracadabra that this was a plausible tale.

Depiction of a triangular ‘abracadabra’ in Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year (1722).

In the late seventeenth century it was still frequently recommended to stave off malaria, or ‘the ague’, as it was known colloquially in Britain. The popular author of self-help books Thomas Tryon included the abracadabra amulet in his Way to save Wealth (c.1695), which advised that it ‘must be writ triangularly, and wear it about your Neck’. As proof of its effectiveness, Tryon added, ‘tis said one Cured above 100 with it’.

The antiquary John Aubrey noted that it was ‘a Mysterious Word, to which the Superstious in former times attributed a Magical power to expel Diseases, especially the Tertian-Ague, worn about their Neck in this manner’.

Yet dismissal of the term as mere superstition was itself nothing new. Johann Rivius, writing in the sixteenth century, noted a ‘superstition… of that ridiculous name Abracadabra: that being written after a certeine manner in a paper, and hanged vpon the necke of him that is sicke of an ague, doth by little and little driue away the disease’.

It may come as little surprise that Victorian writers also readily scorned the term as a trifling curiosity of a more backward time. One encyclopaedia said that ‘the word is, for the most part, used in jest, without any particular meaning, like hocus pocus’. The physician William Leo-Wolf’s dismissive commentary on the recently theorised practice of homeopathy described it as ‘the abracadabra of the nineteenth century’.

The magic extinguished?

Today, the term may indeed have lost any semblance of genuine utility as a medical remedy. To some extent at least, the story of abracadabra’s long life is one of the decline of magic and mysticism surrounding medical healing and the written word. But examples like Lady Gaga’s new song are an invitation to consider the role of belief in our own lives, and to question what it meant for people in the past.

Scepticism about the power of abracadabra evidently has a long history, and we might think of its continuing repetition through the ages as an example of what the historian Will Pooley terms ‘doubt’. For many, the power of the term probably lay somewhere between pure belief and disbelief in realms of uncertainty, reflecting hopes about what the word could do, rather than simple expectation of its transformative power.

The idea that something like magic may be useful or necessary evidently still carries a certain appeal. In Gaga’s song about perseverance, self-improvement and resisting negativity, magic offers a metaphor for overcoming the insurmountable. And what term could be more emblematic of that sentiment than abracadabra?

Nor, in fact, does the original meaning of the term seem to be lost on some fans. As one annotator on the popular song lyrics website Genius.com reminds us, ‘Originating from Mesopotamia, in its roots it stands for ”I create as I speak”, the first known mention of the word was in the book, ‘Liber Medicinalis’, in which Malaria sufferers would wear an amulet containing Abracadabra written in the form of a triangle to cure the disease’.

In Abracadabra, then, we’re presented with not only a remarkably vivid and long-lived example of textual transmission across languages and cultures, but a potent reminder of the importance that magic and mysticism has played in the beliefs and everyday lives of people throughout history. If Lady Gaga’s latest track is anything to go by, magic may still have a role to play for us all ‘in the game of life’.

Sources:

Tom Metcalfe, ‘The ancient—and mysterious—history of “abracadabra”’, National Geographic, 1 March 2024 [behind paywall].

William G. Pooley, ‘Doubt and the dislocation of magic: France, 1790–1940’, Past & Present, 262 (2024), pp. 133–67.

Johann Rivius, A notable discourse of the happinesse of this our age (London, 1578).