Science as a discipline has often suffered from gatekeeping, with the prestige associated with it often reserved for a select few in elite positions. However, there are many examples of individuals who have found subversive ways of accessing, producing and disseminating scientific knowledge. One method of this is through the practice of copying. Let's explore an example of this by looking at some of Gustaf Johan Billberg’s copies of Olof Rudbeck the Younger’s Fogelboken (the bird book), a work filled with hand-painted watercolour illustrations that catalogued the birds of Sweden.

The Original Book: Fogelboken

Before we dive into the copies, let’s discuss the context in which the original book was created. Fogelboken was written by Rudbeck the Younger, son of Olof Rudbeck the Elder, a significant figure in Swedish scientific history. Rudbeck the Elder was the author of the Atlantica works, where he argued that the lost city of Atlantis was located in Sweden (which I have written about here).

In 1695, following in his father’s footsteps, Olof Rudbeck the Younger undertook a scientific expedition to the Sápmi region, located in the far north of the Swedish Kingdom. His voyage was the first scientific journey of its kind to the region. While the Arctic territory made up a large percentage of Sweden’s land mass, it was mainly populated by the indigenous Sámi peoples, and there was little contact between the far north and Uppsala, which was the scientific hub of Sweden at the time. As the Swedish scientific movement grew, they wanted to learn more about the natural environment of the Arctic, so that they could maximise their resource extraction. This journey resulted in two major contributions to Swedish scientific knowledge: the travel account Nora Samolad (1701) and Fogelboken, a collection of hand-drawn illustrations which included drawings of the birds he had seen during his journey.

Rudbeck used these illustrations when delivering lectures in ornithology (or the study of birds). Evidence of the importance of these illustrations to scientific knowledge in Sweden can be seen in the work of Carl Linnaeus, who created the system of binomial nomenclature in the taxonomy of animals and plants used to this day. In this system, organisms are named in two parts, where the first part indicates the genus, and the second part indicates the species. Rudbeck’s illustrations and materials from his lectures were used in the tenth edition of Linnaeus’ Systema Naturae, wherein Linnaeus outlines his classification of species. Clearly, these illustrations were invaluable to the scientists who could access them.

Subversive Science: The Billberg Copy

But how accessible were these images? It turns out, not very. Upon Rudbeck’s death in 1740, his books were sold at auction. Many of his books, including Fogelboken, were acquired by Charles De Greer. De Greer’s private collection was impressive, holding around 8,500 volumes, and it remains almost in its entirety at the village of Lövstabruk in Uppsala. As the manuscript had not been published during Rudbeck’s lifetime and was being held in a private collection, someone would need permission to access De Greer’s collection to obtain the knowledge contained in Fogelboken. That is, unless someone were to make a copy…

This is precisely what Billberg did. Even though he was a lawyer by trade, Billberg had a passion for the natural sciences. This hobby led him to create the ‘Linnéiska Samfundet’ (the Linnean community) in honour of Carl Linnaeus, and he joined the Swedish Royal Academy of Sciences in 1817. He was also a close friend of Carl Peter Thunberg, one of Linnaeus’ old students. It is likely through these connections that he was able to access the De Greer collection.

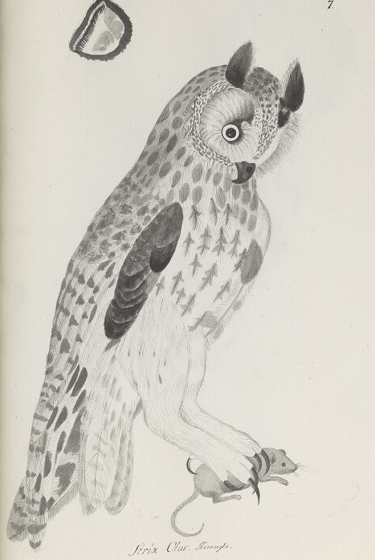

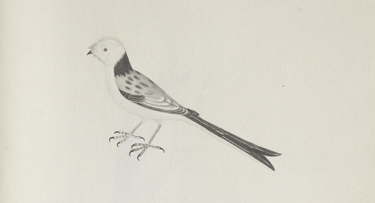

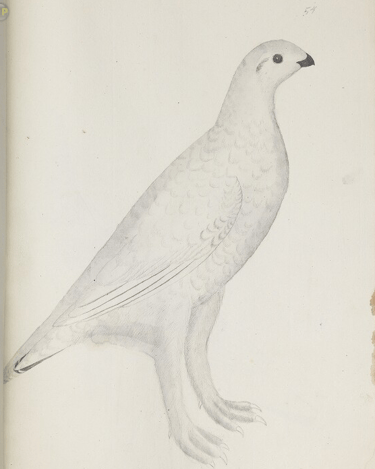

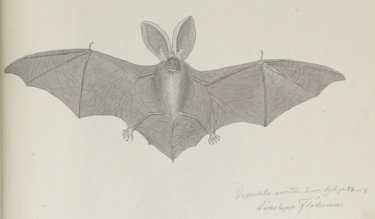

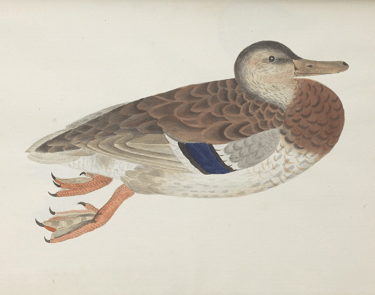

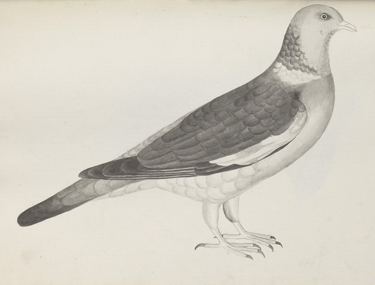

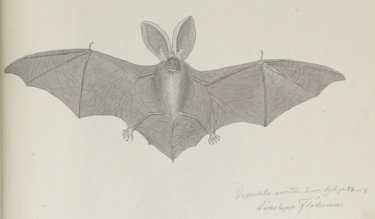

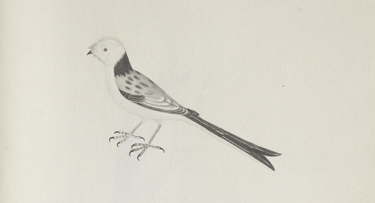

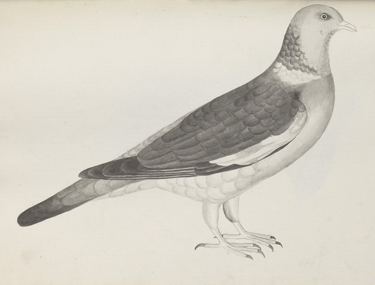

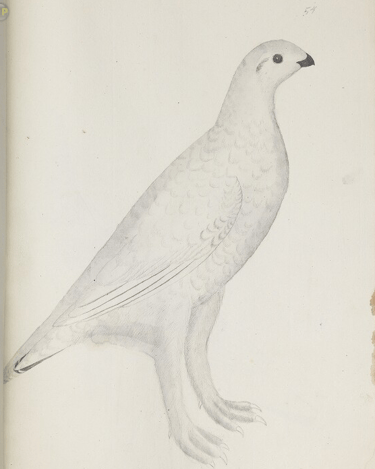

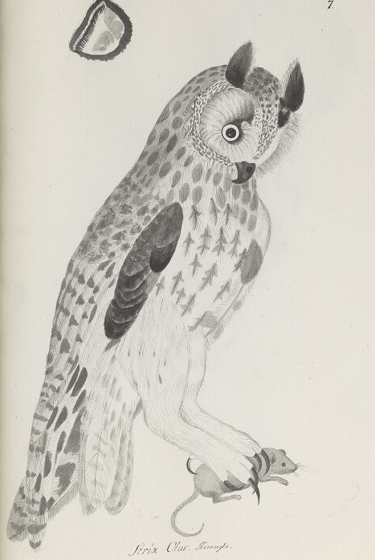

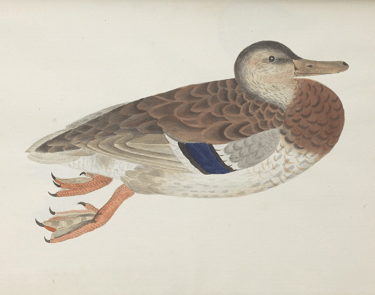

The illustrations by Billberg varied in detail and quality. Most of them are pencil drawings, but some, such as the female mallard (which you can see in the image gallery at the end of this post), were completed with watercolour, like in Rudbeck’s originals. There are approximately 175 bird illustrations, as well as some drawings which depict insects, and even one of a bat. Notice the care with which he replicated the pattern of the feathers, even in the pencil drawings.

In this context, we can think of the practice of copying as a subversive act. By reproducing the illustrations in Fogelboken, Billberg as a non-professional was able to appropriate scientific knowledge that was being held in a private collection for his own use. This act of copying highlights how although scientific knowledge was mainly thought of as the domain of the elite, it was possible to find ways for non-specialists to appropriate scientific knowledge. Billberg appropriated scientific knowledge for his own use, and possibly shared it with his fellow hobbyists (although we have no information confirming this). It is also worth keeping in mind that the concept of plagiarism is a recent concept; in the past, copying within scholarship was an accepted and even encouraged practice.

Fogelboken was published for the first time in 1985 (with an English translation in 1986), but you don’t need to buy a copy or have access to a private collection to take a look at Billgerg’s illustrations, you can find it on the Alvin database here.

Sources

Gustaf Johan. Billberg. Iconographia Olavi Rudbeck junior, Archiater, Med. Professor et Doctor. urn:nbn:se:alvin:portal:record-161649 https://www.alvin-portal.org/alvin/view.jsf?dswid=-2413&searchType=EXTENDED&query=&aq=%5B%5B%7B%22PER_PID%22%3A%22alvin-person%3A8129%22%7D%5D%2C%5B%7B%22SWD_PER%22%3A%22alvin-person%3A8129%22%7D%5D%5D&aqe=%5B%5D&af=%5B%5D&pid=alvin-record%3A161649&c=6#alvin-record%3A161649

Fransen, S., Reinhart, K. M., & Kusukawa, S. 'Copying images in the archives of the early Royal Society', Word & Image, 35:3 (2019), pp. 256–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/02666286.2019.1628629

Hamberg, E. 'The Books of Olof Rudbeck Father and Son at Leufstabruk', in Peter Sjökvist; Marieke Van Delft (eds), A Warm Scent of Books: Private Libraries at Leufstabruk and Beyond. Acta Bibliothecae R. Universitatis Upsaliensis. Vol. LV. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis: 2023, pp. 71–84.