Did a melon really kill Pope Paul II?

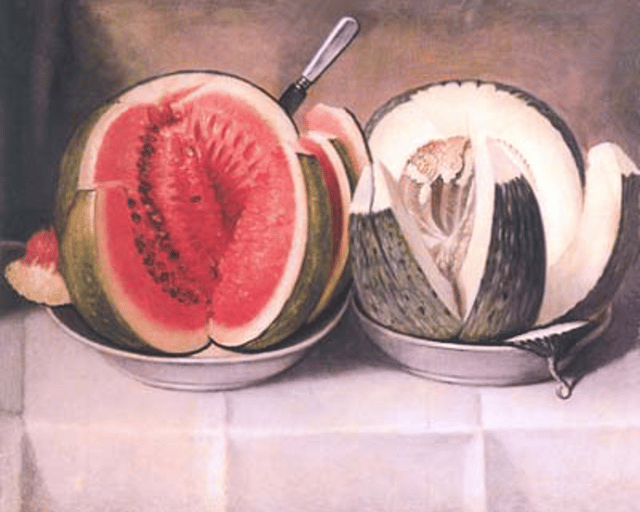

When Pope Paul II died suddenly in the summer of 1471 after overindulging in some melons, people seemed to think that this pesky fruit was what caused it. But why?

While death by melon may seem like a mad thing to suggest, when Pope Paul II died suddenly in the summer of 1471 after overindulging in some melons, people seemed to think that this pesky fruit was what caused it. But why?

It might help us to delve a little deeper into the peculiar circumstances of the pope’s death. Contemporary writer Bartolomeo Platina tells us about the pope’s culinary habits and the last supper that (as he believed) caused Paul’s premature demise:

Another contemporary biography of Pope Paul written by Michele Canensi acknowledged that some people thought the pope might have been poisoned, but Michele was quite sure that poison was not the culprit. He went on to quote the pope’s doctor, Valerio of Viterbo, who said that 54-year-old Paul was rather overweight, got almost no exercise, ‘and enjoyed very humid foods’. This, the doctor warned the pope, may cause him to suffocate suddenly by phlegm. Canensi also described the pope’s fatal dinner for us:

So, the picture is becoming a bit clearer now. We have a middle-aged pontiff with a rather unhealthy lifestyle who liked to eat lots of foods that were considered humid by the science of the time. But what’s wrong with humid food? And why were melons blamed for his death? To understand this, we need to talk about humours.

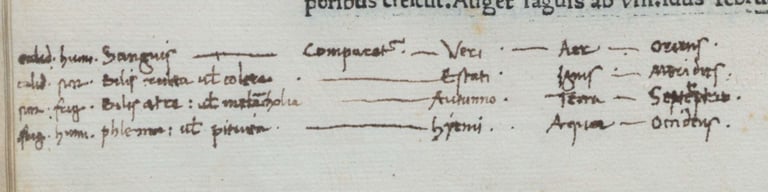

A note scribbled in the margin of a printed edition of De Honesta Voluptate et Valetudine, a book by our Bartolomeo Platina from before, puts it rather neatly:

Blood -------- spring ----- air ----- East

Yellow bile --- summer --- fire ---- South

Black bile ---- autumn ---- earth --- North

Phlegm ------ winter ----- water --- West

Sources

Bartolomeo Platina, Liber De Vita Christi, 1485, p. 133v.

Michael Canensius, Le vite di Paolo II, 1904, p. 175.

Platina, De honesta voluptate et valetudine, 1475, ff. 5v, 17r, 76v. (Digitised by the BNCF: https://archive.org/details/ita-bnc-in2-00000024-001/mode/2up)

Plin. Nat. 19. 23, trans. John Bostock and Henry Riley.

Antonella Campanini, ‘Regulating the Material Culture of Bologna la Grassa’ in Sarah R. Blanshei (ed.), A Companion to Medieval and Renaissance Bologna, 2018, pp. 129-153, esp. 133.

The humours in pre-modern medicine

Premodern medicine was based on a holistic theory which described the operation of the physical body as depending on four liquids, or humours, namely blood, black bile, yellow bile, and phlegm. To massively simplify a hugely complex subject, the healthy working of the body relied on the balance between all four humours. Having one of them in excess temporarily or permanently, could affect one’s mood or even personality. For example, even today, one might describe someone as sanguine (from sanguis, Latin for blood), melancholic (that is, related to black bile), or (less commonly) phlegmatic (having excess of phlegm). Each humour was either hot or cold and wet or dry, and each was associated with one of the four elements, one of the seasons, and one of the cardinal directions.

Much of medicine at that time was about prevention, with particular attention given to what one ingests and excretes. If the humours became too unbalanced it would manifest as disease, and if a medical practitioner diagnosed this as the cause of someone’s illness, she or he might try to rebalance the humours themselves. Bloodletting, for example, is a common example that is somewhat synonymous in the popular imagination with witch doctors and the ineffective treatments of ages past, but it was a perfectly reasonable practice within the framework of humourism. If someone was overly sanguine, removing some of their blood would rebalance their humours. There were of course other ways of falling ill and getting better, and we might talk about those at some other time.

This all sounds very strange and mystical, but what is possibly most astonishing about this theory is how enduring it was. Essentially, from Greek antiquity until more or less the eighteenth century, physicians could recognise the basic framework in the works of colleagues across time and geographical space in a way that seems improbable today. Hippocrates (5th century BC), Galen (2nd century AD), Ibn Sina (or Avicenna, 10th century AD) and our 15th century friend Valerio of Viterbo would probably consider themselves fellow clinicians. But a present-day doctor might struggle to find much common ground with even a Victorian colleague since science has been moving so fast lately. This is certainly not to suggest that theories and practices remained unchanged during humourism’s dominance, quite the opposite, but the overall paradigm of the balance of bodily fluids persisted.

Melons are a health risk

But let’s get back to melons and poor Pope Paul. Melons were a cause for concern even for the likes of ancient Roman writer Pliny the Elder who wrote about pepones (melons) in his Naturalis Historia:

Melons were considered so cold and humid that they could very easily throw one’s humours out of balance, and an unripe melon – which was even more cold and humid – was considered virtually poisonous. This is why, as historian Antonella Campanini found in the Bolognese records of the 16th century, there were some specific regulations against the practice of farmers in the Bolognese countryside who were harvesting unripe melons, buried them in wooden or terracotta pots so they would ripen more quickly, thus creating a real danger to public health.

Now, if we look back to Paul II’s dinner we find a few other foods that could cause a problem; namely fish and cheese. From Bartolomeo Platina’s book De Honesta Voluptate we learn that fish ‘is generally of a cold and humid nature just like the conditions under which they are born’, which seems intuitive enough. Regarding cheese, he was a bit less conclusive since ‘the quality of cheese is dependent on how aged it is. Fresh cheese is cold and humid; salted and hard cheese is warm and dry’. Since, when describing the pope's dinner, Canensi mentioned cheese with other humid foods, it might be safe to assume that it was fresh.

This gives us a sense of an extremely unbalanced dinner with unfortunate results. So, it is clear why eating two whole melons was considered by his contemporaries a fatal mistake (it may even seem insane to us today), but it is very unlikely that melons are the cause of Paul II’s death. We can be quite sure of it because the humours theory has been completely debunked (in large part due to the discovery of germs).

Premodern medicine gets a lot of bad press these days just because it is based on principles that are factually wrong. But even though premodern doctors did not know how to sequence DNA or that T-cells exist, it does not mean we should not respect premodern medicine as a field of knowledge. Medicine was, and still is, an art rather than a pure science (although it is very much driven by science). Physicians always tried and observed, and if something worked, they stuck with it even if they did not quite understand why it worked. And if they found something unexpected, they adapted their theories to try and explain it. The fact that this framework served physicians (many of them extremely clever people) for so many centuries, tells us that even though it was wrong, it was still useful, and in a way, that’s quite good in itself.

He would take extreme pleasure in eating melons, crabs, pies, fish, and salted pork, from which things I believe he got the apoplexy which killed him. Naturally, he ate that day two very large melons and died the following night.

And so, on the day after the feast of St James the Apostle [26 July] he had his dinner in the garden […] and he ate many different fruits and also fish and then cheese…

[melons] when eaten remain on the stomach till the following day, and are very difficult of digestion.

Pope Paul II