For medieval observers, looking closely at the animal kingdom was considered a worthwhile endeavour as it was full of valuable lessons about morality, religion, natural philosophy, and yes, politics. The reason for this relates to a prevalent philosophical opinion, which dates back to antiquity and has persisted until the emergence of modern science, that everything in our world is a reflection of a higher level of reality (Platonic ideas are a classic example). Therefore, studying our world closely could unlock hidden knowledge of this transcendental order. Put more monotheistically, our natural world is part of God’s creation and by examining the Creator’s work, scholars hoped, we could learn about Him.

The best understanding of the cosmos (from the Greek kosmos, meaning order) in the Middle Ages was that God is at the centre of creation and all are hierarchically subjected to Him (God, the angels, saints, then all the rest). This is reflected in a well-ordered human society (emperor/king, nobles, then all the rest) and even in the natural world, as we shall see.

Enter a new genre of books of knowledge dedicated to beasts called bestiaries. These books list important information and contain exempla or stories with moral lessons. Some of the creatures covered in these books were rather ordinary, but some were so exotic that one may even doubt their existence altogether (we’re talking dragons, phoenixes, etc). Here, though, we’ll focus on bees, which certainly do exist.

Bees and the Aberdeen Bestiary

The small, industrious insects who produced honey and wax, lived in harmonious communities, and upheld monarchical rule, were considered highly respectable by medieval learned people. But instead of Isidore of Seville, John of Salisbury or Thomas Aquinas, all eminent scholars who showed some interest in bees, let us look at the Aberdeen Bestiary.

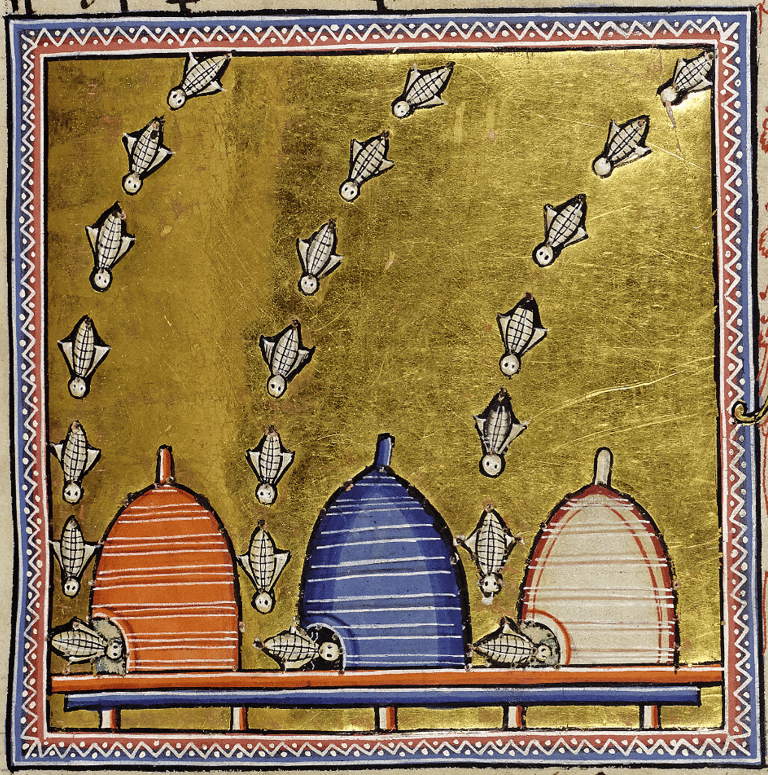

The Aberdeen Bestiary is an opulently illuminated (i.e., decorated with gold leaf) manuscript which probably dates from the twelfth century and has English provenance (i.e., origins), was probably commissioned by the king or a high-ranking nobleman and ended up in the royal collection. It was later gifted by a librarian of James VI and I to Marischal College which later became part of the University of Aberdeen. The manuscript remained in Aberdeen, was scanned, translated and made freely accessible to the public here.

There’s a lot of interesting (and quirky) information about medieval beasts in general (the mythical bonnacon is a particular delight) but some observations of the humble bee are just as outlandish. For example, the explanation for the Latin name for bees, apes, was that because they were thought to be born without feet, hence, a (no) + pes, (Latin for foot). It was also thought that bees could be ‘created’ by ‘beating the meat of dead calves’ an action which generated worms out of the putrefied blood which later became bees. It was quite important to choose your dead flesh carefully, as if you beat a dead horse you may get hornets rather than bees, mules would produce drones, and dead donkeys would give out wasps.