Last year the Daily Mail reported that ‘Inflation is now so bad people are nostalgic for 2021, when an avocado cost $1 instead of $2.50, and a dozen eggs were $1.60 not $4.21’. As the tabloids know all too well, everyone can relate to the feeling of yearning for cheaper times, when pints at the local pub were less that a pound, and Freddos were 10p rather than the eye-watering 49p that they reportedly cost today.

Such inflation inevitably provokes more serious concerns about the rising price of essential foods, fuel and housing. In the last couple of years, a cost of living crisis, soaring profits of supermarkets and energy companies and July’s general election have once again brought the price of everyday necessities into sharper focus. Rising costs can elicit a variety of emotions from anger to anxiety as we worry about making ends meet. But they can also evoke nostalgia. And as it turns out, this phenomenon is nothing new.

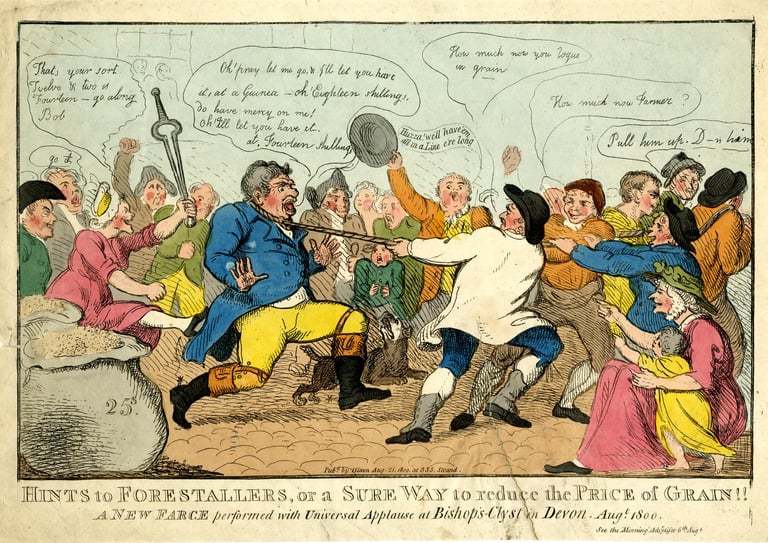

Hints to forestallers, or a sure way to reduce the price of grain!! (1800)

Here, and in every other part of the country, the prices of provisions were far lower about 30 and 40 years ago than at present. The old people say, that in their time the boll of meal sold for 6 merks [£4] Scots… and other necessaries in proportion. But these matters have since undergone a vast change; every article has been increasing in value, and the difference of prices is now sensibly felt.