In 1773, during their now famous tour of the Western Isles of Scotland, Samuel Johnson and James Boswell made a pit stop at a settlement called Aonach in Glen Moriston, near Inverness. As Johnson later recalled, a girl who served them tea ‘engaged me so much’ that he decided to give her a present. Having only what he could source in Inverness to hand, the gift was a copy of the highly popular maths textbook, Cocker’s Arithmetick.

Despite Boswell’s surprise, Johnson justified his giving of a practical gift. ‘When you have read through a book of entertainment’, he said, ‘you know it, and it can do no more for you; but a book of science is inexhaustible’. When this story was later recounted to a group of ‘Several ladies, wishing to learn the kind of reading which the great and good Dr. Johnson esteemed most fit for a young woman’, it caused fits of laughter. As Boswell noted in his biography of Johnson, ‘My readers, prepare your features for merriment. It was Cocker's Arithmetick! Wherever this was mentioned, there was a loud laugh’.

Perhaps it’s easy enough to detect the humour in a literary giant like Johnson engaging with a lowly arithmetic primer, or maybe the joke was a prejudiced slight at the prospect of a young female servant learning arithmetic. But to me the extent of hilarity occasioned by this situation has always been somewhat perplexing. Why was the most successful arithmetic textbook of its day the butt of a joke? What was so funny?

An early modern bestseller

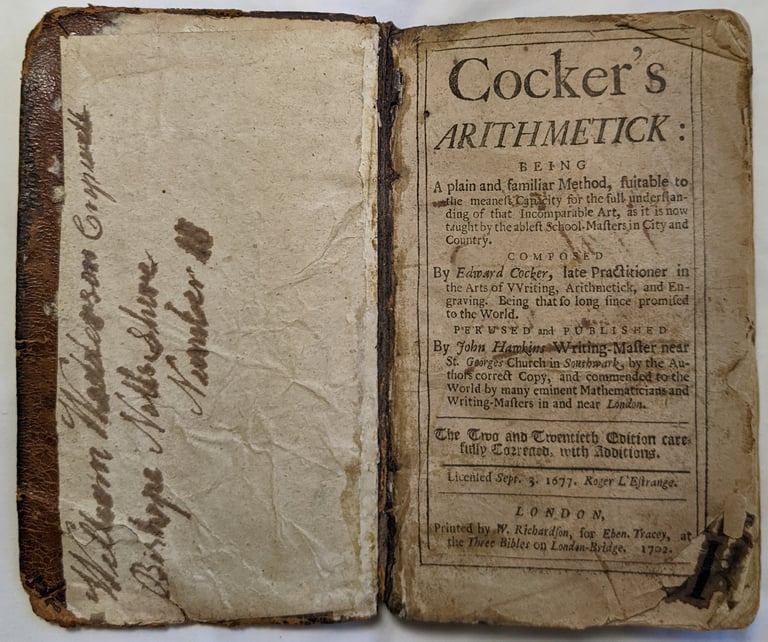

On the surface, Cocker’s Arithmetick was hardly riveting stuff. It taught the basics of arithmetic – addition, subtraction, multiplication and division – presented as a set of ‘rules’ to be memorised with many worked examples that began with very basic problems that became increasinging difficult. Yet its popularity is remarkable by any standards. Written by Edward Cocker, a London-based teacher of writing and arithmetic, the book was first published posthumously in 1678. It was then reissued continually for decades after, not only in London, but also Dublin, Edinburgh and Glasgow. Its final edition appeared over a century later, in 1787, and by my own (conservative) estimate, it saw at least seventy editions.

Dr Johnson used some of Cocker’s definitions for arithmetical terms in his magisterial Dictionary of the English Language (1755). Prominent figures known to have learned from the book include founding father of the United States Benjamin Franklin, the mathematician Thomas Simpson, the poet John Clare and the radical reformer Samuel Bamford. Its popular recognition was so great that the phrase ‘according to Cocker’ came to mean anything that was exactly right or ‘textbook’.

I first wrote about Cocker’s Arithmetick in a 2022 article that explored the reasons for the book’s remarkable success, arguing that its low cost, accessible content and situation within the mass market for cheap print ensured that it became a best-seller during an era when demand for arithmetic books was skyrocketing. It wasn’t affordable to everyone, costing more than a day’s wages for the lowest-paid workers, but the price of a shilling put it among the cheapest arithmetic books.

Chapters on commercial arithmetic skills in the second half of the text hinted at its target audience: aspiring businesspeople. It was this facet of Cocker’s appeal that ensured its enormous popularity. The book appeared at just the moment when the currency of arithmetic was exploding thanks to rising literacy and the emergence of a society oriented around commerce, consumerism and sociability. Buying Cocker’s Arithmetick represented a ticket to this new world.

While nineteenth-century historians of mathematics slated the book for teaching arithmetic as a set of hard rules rather than explaining its underlying logic, Cocker’s success surely demands that we take it seriously as a piece of didactic literature. How, then, do we reckon with the fact that some people in the later eighteenth century saw it as an object of humour?

Getting the joke

Understanding that Cocker’s Arithmetick was a topic of amusement for some people recalls Robert Darnton’s famous observation in The Great Cat Massacre (1984), that when we observe something such as a joke that appears alien or incomprehensible to us, it may be a good point of entry into the mindsets and attitudes of people in the past. Viewing Cocker’s Arithmetick in this light exposes the multifaceted nature of the book’s reception, and perhaps attitudes towards numerical knowledge in general. In this case, while the ‘knowledge’ of arithmetic itself remained fixed in a book that changed little in its century-long life, the social value of this knowledge varied markedly among different people and over time.

When it first appeared, it quickly became popular because it exploited a gap in the market. It was cheaper than other books, and offered an effective means of learning at a time when schooling in arithmetic was still quite sparse. By the second half of the eighteenth-century, as newer titles began to supersede Cocker’s popularity, it remained a widely used book. Yet it was at this time that the very popularity of the book seems to have become an object of amusement.

In Arthur Murphy’s 1756 play The Apprentice, one character is instructed to ‘Get Cocker’s Arithmetick – you may buy it for a Shilling on any Stall – best Book that ever was wrote’. Surely this was sound advice, but the element of hyperbole hints at the way in which the extent of the book’s popularity could be ridiculed. There must also have been some exaggeration in the early nineteenth-century bibliographer Thomas Frognall Dibdin’s assessment that Cocker was ‘a work which has probably made as much stir and noise in the English world, as any – next to the Bible’.

The success of Cocker’s Arithmetic was self-perpetuating: the more it was talked about, the longer it continued to be produced and the more Edward Cocker himself became proverbially associated with matters of arithmetic. In turn, the extent to which the book’s popular recognition so vastly outgrew its status as a humble textbook of basic arithmetic must have seemed ever more ludicrous. Perhaps then, for those hearing tales of Boswell and Johnson’s tour of the Western Isles, seeing one of the era’s great literary figures dealing with Cocker’s Arithmetick was simply the realisation of this joke par excellence. If a mundane book of basic arithmetic could be both wildly successful and an object of humour, it demonstrates that in order to fully understand past forms of knowledge, we need to interrogate the evolving cultural values that surrounded them.

Sources

James Boswell, Boswell’s Life of Johnson, ed. George Birkbeck Hill (6 vols., Oxford, 1887), vol. V, p. 157.

Edward Cocker, Cockers Arithmetick, Being a Plain and Familiar Method Suitable to the Meanest Capacity for the Full Understanding of that Incomparable Art, as it is now Taught by the Ablest Schoolmaster in City and Countrey (London, 1678).

Robert Darnton, The Great Cat Massacre and Other Episodes in French Cultural History (London, 1984).

James Fox, ‘Numeracy and Popular Culture: Cocker’s Arithmetick and the Market for Cheap Arithmetical Books, 1678–1787’, Cultural and Social History, 19 (2022), pp. 529–545.

Samuel Johnson, Letters of Samuel Johnson, LL.D., ed. George Birkbeck Hill (2 vols., New York, 1892), p. 243.