Remembering the past: sex and scandal on Guy Fawkes Night

What does a scandalous court case from 1700 reveal about the way the Gunpowder Plot was remembered in eighteenth-century England?

James Fox

11/5/20245 min read

324 years ago, just before Guy Fawkes Night 1700, two women named Alice Wilson and Martha Goodbarne visited the house of Jane Sudgen in Halifax, Yorkshire, to drink and gossip. The topic of conversation was a local scandal. They believed that a married woman named Ruth Edwards had committed adultery with a tax collector. Rumour had it, Edwards was a ‘Whore and a dishonest woman of her Body’.

These words were recorded because twenty-year-old Mary Caward, who was probably a servant in Sugden’s household, was asked to recall the conversation in court. Ruth Edwards refuted these allegations and now she was suing Alice Wilson for defamation.

In the eighteenth century, England maintained an active system of ecclesiastical courts inherited from the Middle Ages. Policing sexual misconduct – and defamatory accusations thereof – were daily tasks of these authorities. Adultery was an especially grave charge in a society in which reputation was so crucial for economic as well as social standing. And so for women like Ruth Edwards, who had been ‘much Scandalized and abused’ as a result of the rumours, its seriousness was enough to warrant legal action to clear her name.

Courtroom of Chester Cathedral

The time of events

At the risk of disappointing some readers, however, this article is not about sexual scandals or legal drama. What concerns us here is a particular detail in the testimony of the other witness in this case, a fourteen-year-old saddler named Jeremy Gledhill. The testimony Jeremy gave, at least according to the court records, was much the same as Mary Caward’s, but it differed in one crucial respect.

To the question of when this scandalous meeting had occurred, Mary had given a numbered day of the month: ‘the fourth of November last past’. But when Jeremy was asked the same question, he responded not with a day of the month but with a different form of date: ‘about gunpowder treason-day last past’.

Jeremy Gledhill and Mary Caward both remembered when this conversation had occurred, but whereas Mary opted for the calendrical terms familiar to modern audiences, Jeremy’s answer dated the conversation in relation to an important milestone in the yearly calendar: the anniversary of the Gunpowder Plot.

Everyday temporalities

Accurate telling of the time was an important form of knowledge in the pre-modern world, whether for the coordination of daily routines, organising work and trade, or pursuits such as astrology and navigation. Everyday life was not, as is sometimes assumed, bereft of the ubiquitous presence of clock and calendrical time.

But as examples like this defamation suit demonstrate, the ways people reckoned time in the days before modern standardisation could vary significantly from one person to the next. The moment court witnesses were asked about the date of crimes as the scribe recorded their testimony is one of the rare moments when this vast and colourful array of temporal language becomes visible.

These records reveal that the standard numerical terms of the calendar and clock were just one way that witnesses dated events. In fact, in England before the eighteenth century, such dates were used comparably rarely by witnesses. Instead, people commonly related the events in question to widely observed temporal markers such as saint’s days and other religious festivals. For example, one gentleman on the docket soon after Jeremy Gledhill dated a defamatory conversation ‘on Sunday next before Easter-day’.

Gunpowder treason and plot

It was within this context that Gledhill remembered the scandalous discussion at Jane Sudgen’s house on ‘gunpowder treason-day’, an old name for what is now known as Guy Fawkes night. In the decades after the infamous attempt of Fawkes and his co-conspirators to blow up the Houses of Parliament in 1605, religiously-motivated commemoration of the foiled attempt at high treason became an important annual event.

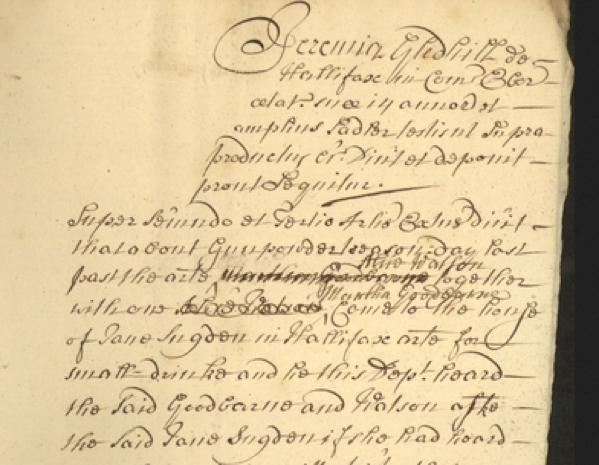

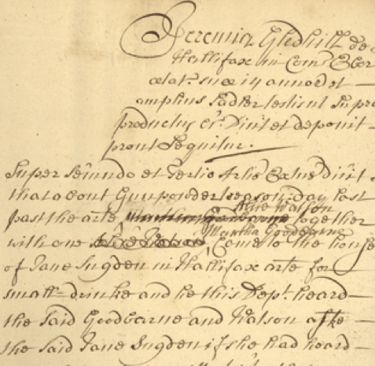

The recorded deposition of Jeremy Gledhill, 1701. Image: Borthwick Institute for Archives.

Henry Perronet Briggs, ‘The Discovery of the Gunpowder Plot and the Taking of Guy Fawkes’, c.1823

From 1606 it was an officially sanctioned day of remembrance on which ministers preached to give thanks for the plot’s failure. Through the seventeenth century it became embedded in public consciousness as an anti-Catholic showing of allegiance to the Anglican faith, especially in times of unrest. Bell ringing, bonfires and burning effigies of the Pope and the Devil were ubiquitous annual occasions and the subject of printed news pamphlets. For Jeremy Gledhill, then, gunpowder treason day was a useful milestone in relation to which he could date the conversation that he was being questioned about.

In fact, though, this case disguises significant changes that were taking place in the ways people understood time around 1700. From the late seventeenth to the mid-eighteenth century, the standardised use of numerical clock and calendrical times, previously a rare way of describing the time in English court depositions, became by far the most common way in which witnesses dated past events. At the same time, ownership of clocks was increasing substantially as they became more accurate and affordable. The ability to read was also growing steadily, allowing more people to digest calendars or almanacs.

Annual almanac with monthly calendar, 1777

For historians interested in past forms of knowledge, the ways people told the time and remembered events are an important but potentially elusive topic. For that reason, witness testimonies like that of Jeremy Gledhill offer an especially valuable window into common ways of remembering the past, and the cognitive and linguistic apparatus which conditioned people’s understanding of time.

The fireworks and bonfires that fill our skies on the fifth of November are a reminder that annual days of commemoration have not entirely disappeared from our sense of the year’s shape. But if Jeremy Gledhill’s witness testimony regarding an event on ‘gunpowder treason-day’ belonged to a fast fading form of timekeeping, Mary Caward’s use of the calendar’s numerical terms was undoubtedly a sign of things to come.

Sources

Borthwick Institute for Archives, York, CP.I.60, Edward v Watson (1701).

Borthwick Institute for Archives, York, CP.I.91, Darley v Read (1701–02).

James Fox, ‘Meanings and uses of numeracy in Scotland and northern England’, University of St Andrews PhD thesis (2024), ch. 4.

Keith Wrightson, ‘Popular Senses of Past Time: Dating Events in the North Country, 1619–1631’, in Michael J. Braddick and Phil Withington (eds.), Popular Culture and Political Agency in Early Modern England and Ireland (Woodbridge, 2017), pp. 91–107.