24th June 1694. Midday. A group of young women, perhaps twenty-two or twenty-three in number, rummage in the dirt of a field on the outskirts of London. They hope to find coals beneath the roots of plantains to put under their pillows as they sleep. Do this, they’ve heard, and their future husbands will appear to them in their dreams.

**

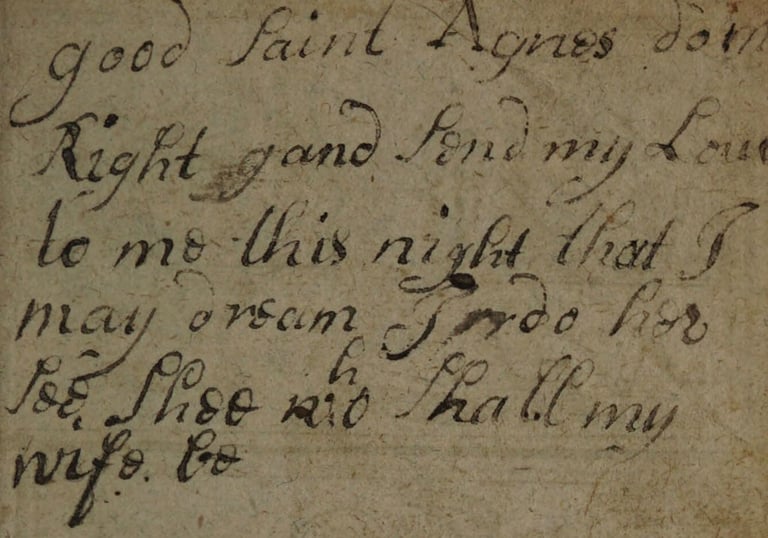

A January night, early eighteenth century. A starry-eyed young man pens a prayer in the front of a one-shilling booklet of magic tricks. ‘Good Saint Agnes’, it reads, ‘do me Right and Send my Love to me this night, that I may dream I do her see, shee who shall my wife be’.

**

As these episodes suggest, hopes of future romance played regularly on the minds of young adults in early modern Britain. The sight of women digging for coals was observed by the prolific seventeenth-century antiquary and naturalist John Aubrey. A connoisseur of all things folkloric, he was fascinated by the rituals, sayings and proverbial wisdom passed down through generations, of which charms to induce visions of future spouses were a prominent example.

Ribwort plantain, or plantago lanceolate, to use Linnean binomial nomenclature.

Plantains (not the fruit but an English species of flower) were among the most widely recommended ingredients in folkloric medicinal recipes and were also used for healing wounds and skin complaints. Digging for coals beneath them, especially at midday on 24th June, the traditional date of midsummer eve, was reported to have a wide range of possible advantages, including curing plague and safeguarding the finder from lightning strikes.

Influencing dreams was a common purpose of magical charms and rituals. Dreams were taken seriously, believed to be capable of revealing the future, or elements of one’s true character. Many literate people liked to make note of their dreams, and the interpretation of such visions was a regular source of business for astrologers.

‘The Eve of St. Agnes’ by John Everett Millais, c.1863.

Another dream-inducing ritual ‘handed down… by Tradition’, Aubrey reported, was to be performed on 21st January, the day of St Agnes, patron saint of girls and engaged couples. This involved sticking a row of pins in one’s sleeve, saying the Lord’s Prayer between each pin, ‘and you will Dream of him or her you shall Marry’.

A variation of the St Agnes’s eve ritual known in Derbyshire required a day of fasting before lying on one’s left side and repeating a rhyme to St Agnes three times. A Scottish version of the rhyme went:

Agnes sweet, and Agnes fair,

Hither, hither, now repair,

Bonny Agnes let me see

The lad who is to marry me.

‘To procure Love’: practical advice on finding a spouse

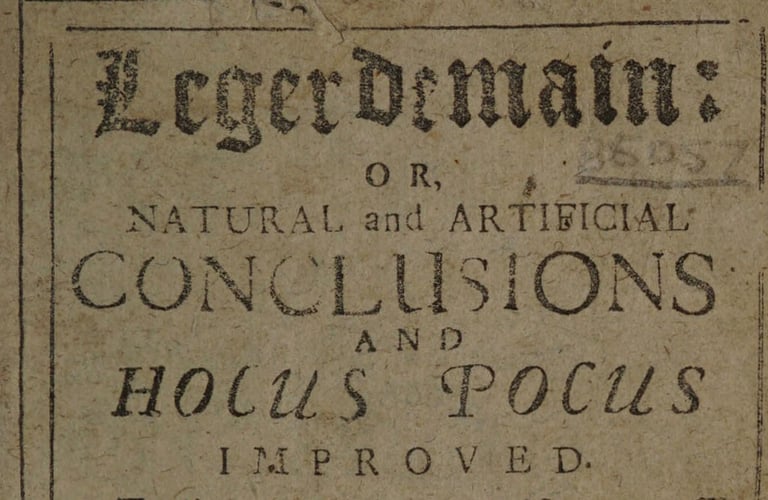

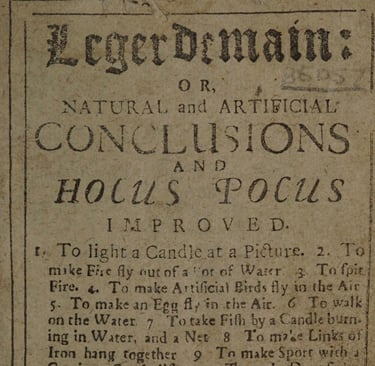

It was another prayer to St Agnes that provides the second example that opened this post. The identity of our hopeful husband-to-be is unknown, but the book in which he penned his prayer was a now-rare copy of Thomas Hill’s magic manual Legerdemain: Or, Natural and Artificial Conclusions; and Hocus Pocus Improved, printed around 1716.

The poem copied into Hill’s Legerdemain, c. 1716.

Manuals on conjuring tricks, sleight of hand or ‘legerdemain’, and the interpretation of dreams, had been a mainstay of English booksellers since the later sixteenth century. By the turn of the eighteenth century, many of these manuals were highly accessible, costing as little as four or six pence.

Their popularity paralleled the rich oral tradition by which folktales and practical advice were passed down, as documented so enthusiastically by Aubrey. Though the seriousness with which magical and occult charms were taken had surely waned by the eighteenth century, when this book-owner jotted his inscription, apparently anything was worth trying in hope of finding a wife. That was, after all, serious business indeed.

The verse penned by the hopeful husband-to-be in fact echoed closely one for St Thomas, whose day is 21st December, as recorded in a popular contemporary collection of folk sayings and remedies entitled Mother Bunch's closet newly broke open (1685). It went:

Good St. Thomas, do me right,

And bring me to my love this night;

That I may view him in the face

And in my arms may kind embrace.

Perhaps it was from this very book that our writer borrowed his verse, subbing in St Agnes as occasion on the liturgical calendar demanded.

The early eighteenth-century edition of Hill’s Legerdemain that bore his inscription doesn’t itself contain anything on dreams, but it wasn’t entirely bereft of dating advice. ‘To procure Love’, it suggested, put ‘a Ring into a Swallow Nest, or Sparrows Nest’, and let your intended lover wear it. In any case, the choice of this owner of the book to note a St Agnes prayer within its pages is suggestive of an enduring perception of the relationship between magic, spirituality and the fate of individuals.

These magical attempts to conjure up images of future romantic partners may seem alien today. But there is surely something similarly ritualistic to be seen in the habitual attendance of dance halls in mid-twentieth century Britain, where, it’s estimated, 70% of couples met, or today’s algorithmic dating apps. If the hope of future romance is indeed a tale as old as time, then it seems that ritualised ways of cultivating it have never entirely disappeared.

Sources

John Aubrey, Miscellanies upon the following subjects collected by J. Aubrey, Esq. (London, 1696).

Adam Fox, Oral and Literate Culture in England, 1500–1700 (Oxford, 2000).

Keith Thomas, Religion and the Decline of Magic: Studies in Popular Beliefs in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century England (London, 1971).

Wellcome Collection, EPB/A/28751, Thomas Hill, Legerdemain: or, natural and artificial conclusions and hocus-pocus improved (London, [1716?]).