In a previous post James told us about a Scottish landowner who systematically recorded the dreich Aberdeenshire weather in her diary. This fascinating source teaches us about historical experiences and perceptions of the weather, but sometimes the weather was recorded much more publicly.

Weather can certainly leave its traces on the streets, if only for a short while. By doing so, it shapes the daily lives and experiences of individuals who, like Janet Burnet, would notice and remark on it. But some extreme weather events leave such an impression on communities that they commemorate them permanently on buildings and monuments.

High winds in Cologne

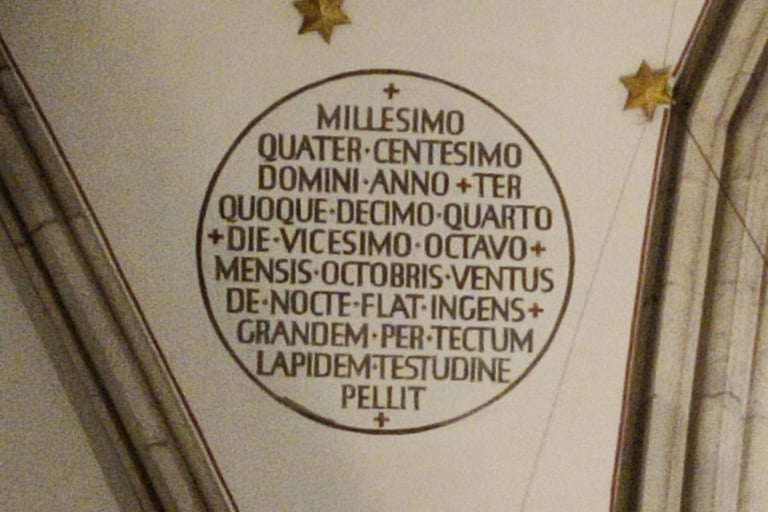

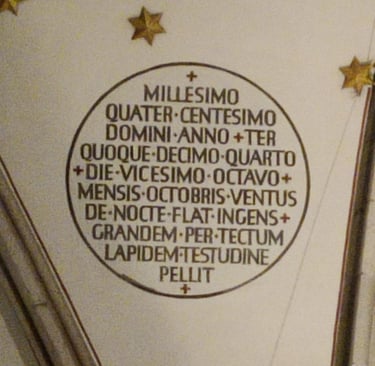

For example, let’s look at the cathedral of the German city of Cologne. Inside this magnificently large gothic church you may notice a curious inscription on one of the vaults.

It reads:

+ Millesimo quater centesimo Domini anno + ter quoque decimo quarto + die vicesimo octavo + mensis Octobris ventus de nocte flat ingens + grandem per tectum lapidem testudine pellit +

And in translation:

In the year of the Lord fourteen hundred and three-times-fourteen on the twenty eighth day of October a mighty wind blew in the night and knocked a large stone through the roof of the vault

You may notice the slightly irregular dating system here, expressed as a simple maths problem (1400 + 3 ∙ 14), which – a calculator reliably informs me – results in 1442. Apart from being a curiously phrased inscription, we can also regard it as an invitation to think about the sort of wind that can dislodge a large stone and send it through a building’s roof, and how extraordinary it must have been.

Buildings are prone to damage however robust they may seem to us; bell towers sometimes collapse, houses catch fire, stained glass windows shatter, and roofs crumble down. They are then repaired, replaced, or removed altogether, but unless the damage is connected to an event that significantly affects the local community, it’s quite rare that it would be commemorated in such a way.

Floods in Florence

Let’s look at another example where the streets can tell us about historical weather. This time we’re in Florence, and it’s the rain that’s the problem. Florence is nestled amongst the Tuscan hills and has the majestic river Arno running through it. The river was important for supplying power to mills and industry as well as for Florence’s trade, as it links the inland city to the Mediterranean. But the Arno could also be quite destructive when it (occasionally) flooded the city.

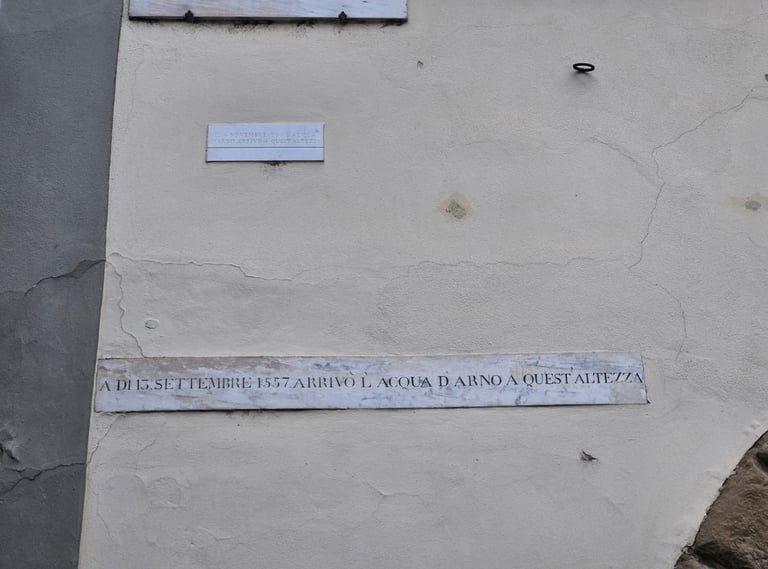

Standing in the north-west corner of Piazza di Santa Croce, facing away from the church and bustling piazza, we are confronted with this seemingly uninteresting house.

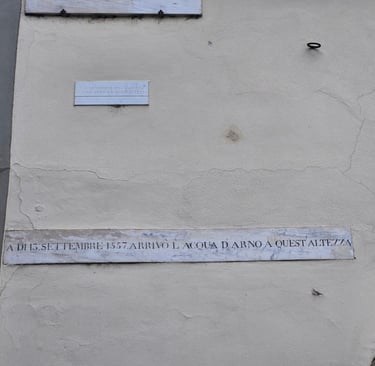

The larger one reads: ‘A dì 13 settembre 1557 arrivò l’acqua d’Arno a quest’altezza’

It tells us that: ‘On 13 September 1557 the water of the river Arno reached this height’.

As you can see, this is well above the height of the entrance door! Such a flood would have affected people’s lives, livelihoods and property. This flood must have been a major event on the life of the community, which is why it got commemorated in one of the city’s most important public places.

The smaller plaque above it tells of a similar but possibly even more destructive story from the most recent flood on 4 November 1966, which caused damage to the city’s famous paintings, sculptures, and historical records in its museums, libraries, and archives. This story deserves its own separate retelling, so we will have to come back to it another time.

So while puddles dry, snow melts, and trees felled by the wind regrow, if a weather event touches the life of a community in a profound way, they will make sure that it is commemorated in the urban environment. This speaks not only to practices of commemoration and the endurance of public memory, but more broadly to the fact that our cities are essentially open-air history books – if we know where to look.