We’ve already written in a previous blog post about the subject of ignorance, a socially created absence of knowledge. While in some situations it may be preferable not to know something, there can also be grave consequences not only for lacking knowledge, but also for failing to use it in the right way.

To explore this idea, let’s dive into a financial dispute that took place in Scotland’s highest civil court, the Court of Session, in the late eighteenth century. I first began looking at the case when searching for early modern account books during my research on the social history of numeracy. One example was a manuscript kept in the 1760s and 1770s by an innkeeper named Thomas Wilson from Kelso, near the Anglo-Scottish border. This book was orderly and well kept, listing incoming and outgoing sums of money, all added correctly down to the last half penny. Hence the question: why was it preserved as evidence in a legal dispute?

Cracking the case

After a long dig through other documents from the Court of Session archive, I had my answer. In 1761 a local landowner named John Jerdan inherited a tanning works in Kelso from his late father. At this time Kelso was a centre for the production of leather goods, with some 147 shoemakers producing 30,000 pairs a year by 1794. Jerdan realised he had a potential cash cow on his hands, and so decided to continue producing leather, selling his output wholesale to the man who had run the business on behalf of his father, the innkeeper Thomas Wilson.

It was a win-win situation. Jerdan got rid of large numbers of animal hides, while Wilson retailed them for a handsome commission. When their partnership finally concluded in the mid-1770s, they decided that their debts to each other were roughly equal and no more was said of them. So it must have come as quite a shock to Jerdan when, over a decade later, he was summoned to court, accused by Wilson of owing him some £400 (roughly £30,000 in today’s money!).

Enter the account book. The basis of Wilson’s case was the manuscript that now resides in the archives at Edinburgh. Jerdan claimed that he hadn’t kept accounts during their partnership, but Wilson came forward with these well-kept and complete books detailing their business from 1768 to 1771. In the first half of that account book, each page listed Wilson’s debts for a year, most incurred from the acquisition of hides from Jerdan, totalling precisely £1312 and 7½ pence.

The second half in turn recorded sums owed to Wilson by Jerdan, including costs for ale drank at his inn, adding up to £1706, 6 shillings and 4¼ pence. Remember that this was the era of pre-decimal currency in which a pound was made up of twenty shillings or 240 pence, and there were even denominations of quarter-pennies (sometimes known as farthings). So when Wilson balanced these debts exactly to £394, 5 shillings and 8¾ pence, it reflected no small command of arithmetic.

So far, so legitimate. But there was just one problem: the debts recorded in this book were completely made up.

Cooking the books

When the court examined Wilson’s books, they found that they were ‘a palpable fabrication, being evidently framed at one sitting… written with the same pen and the same ink, though apparently stating the transactions of three years, by entries from day to day’. Wilson had simply produced the book at a later date rather than over years of business, and there was no written evidence nor witnesses to back up anything that had been said.

It transpired that in the years since his partnership with Jerdan, Wilson had fallen on hard times and this appeared to be a less-than-honest attempt at recovery. After four years in court, Wilson finally admitted his fraud and the case was thrown out in 1792.

Among the many eighteenth-century account books I’ve looked at, Thomas Wilson’s stands out for two reasons. One is that they were entirely fake. While honest mistakes were common in accounts and fraud was a perennial threat, books that were completely fabricated seem to have been exceptionally rare. Even the court found Wilson’s case to be ‘extremely singular’.

The other reason is the fact that they were so neatly kept and had an overall balance calculated across the entire book. Most accounts kept by ordinary tradespeople and retailers at this time did not involve a great deal of calculation. Often accounts simply recorded debts with no attempt to reckon a balance at all. In genuine working documents, it’s common to find mistakes, ink blotting and entries that are crossed out or incomplete. For the very reason of its irregularity, then, Wilson’s book provides a unique vantage point on the forms of knowledge that underpinned economic relationships in eighteenth-century Scotland.

Legitimate knowledge

The way Wilson and Jerdan had actually conducted their business, as detailed in their trial records, was more typical. They recorded payments on loose papers that were soon lost and when their business concluded, they mutually agreed their debts to each other were roughly equal, and no calculation of every minute expense was necessary.

Such activities were more common in this age of only partial literacy, a shortage of physical currency and an economy heavily dependent on trust and ethical concerns: what is often known as a ‘moral economy’. Wilson’s accounts were closer than most to the way that textbooks said they ought to be kept, with a sum total calculated across the entire book; perhaps it was for that very reason that to the court examiners they stood out like a sore thumb.

The case of Thomas Wilson, therefore, offers some valuable lessons. The old dictum, ‘love documents, but don’t trust them’, clearly applies here. Only by reading the records surrounding this account book is it clear that it was a fabrication. Wilson’s accounts also demonstrate the importance of reading against the grain of modern assumptions about what ‘legitimate’ knowledge may have looked like in the past. Wilson evidently believed a certain form of accounting would be the most convincing to the court, yet this attempt to keep a fully balanced account, in the manner prescribed by textbooks, was exactly what marked him out as unusual. Above all, then, this case of fraud shows us that it was not simply possessing knowledge that was important, but knowing when and how to use it in the right way.

The ability to transact effectively in a highly social and moralised economy was one of the most important forms of knowledge possessed by people at all levels of society in the pre-modern world. Unfortunately for Thomas Wilson, he got it all wrong. And so, somewhat ironically, it is his spurious account book that gives us a particularly vivid reminder of how economic relations really worked.

Sources:

Edinburgh, National Records of Scotland [hereafter NRS], CS96/3835, Thomas Wilson, innkeeper, Kelso. Account books (1768–74).

NRS, CS228/W/4/27, ‘Information for John Jerdan Feuer in Kelso’ (1792).

John Sinclair, The Statistical Account of Scotland (20 vols., Edinburgh, 1790–99), vol. X, pp. 586–87.

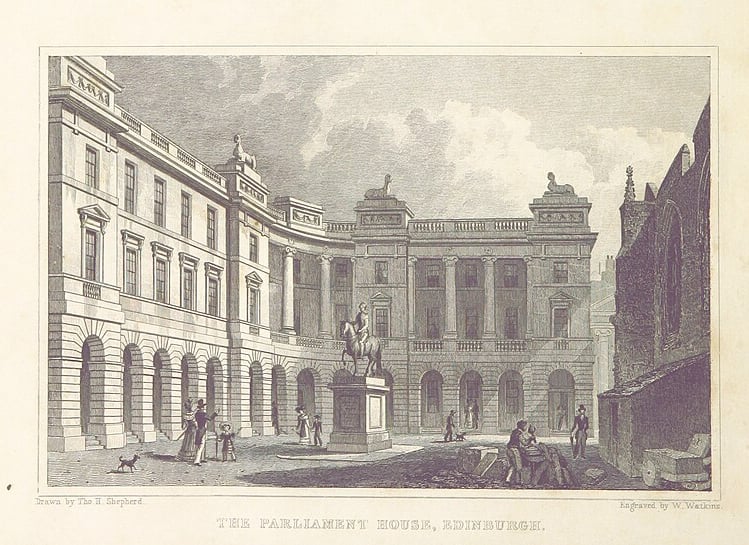

Parliament House, Edinburgh, where Wilson was summoned to court.