Each election of a new Catholic pope is pretty much guaranteed to capture the attention and imagination of people from all faiths or none. It is secretive and mysterious (quite literally, as the process is said to be guided by the Holy Spirit) and is a political event as much as it is theological; the cardinals are electing a head of state after all. Waiting in St Peter’s square for the white smoke to rise from the chimney of the Sistine Chapel, signifying that a new pontiff has been chosen, is familiar not only from the news but from recently released critically acclaimed films as well. One question remains, though, why do the cardinals need to be locked in with a key to elect a pope?

Despite the fact that popes have been selected in one way or another for the better part of two millennia, the word conclave (from the Latin, cum clave meaning ‘with a key’), can be traced as far back as the Middle Ages, specifically the thirteenth century. It emerged from a rather unfortunate event which shaped all following papal elections.

The first conclave

After pope Clement IV died in November 1268 while staying in his palace in Viterbo, a charming city in northern Lazio (just north of Rome), cardinals who were with him in town got together to elect his successor. But this proved to be a rather difficult task. A deadlock between the French and Italian cardinals made it impossible to find a candidate who had the necessary majority. This went on for nearly three years(!) and had such a destabilising effect on European geopolitics and the life of the faithful that the good people of Viterbo locked the cardinals in their palace until they were open enough to the benign influence of the Holy Spirit as well as their earthly discomfort to elect Gregory X in September 1271. Thus, the longest papal election in the history of the Church was finally concluded.

One of the cardinals who attended was quoted as saying: ‘Gentlemen, we should take off the roof of this hall, as the Holy Spirit cannot come to us through the roof’, revealing how desperate the situation had become.

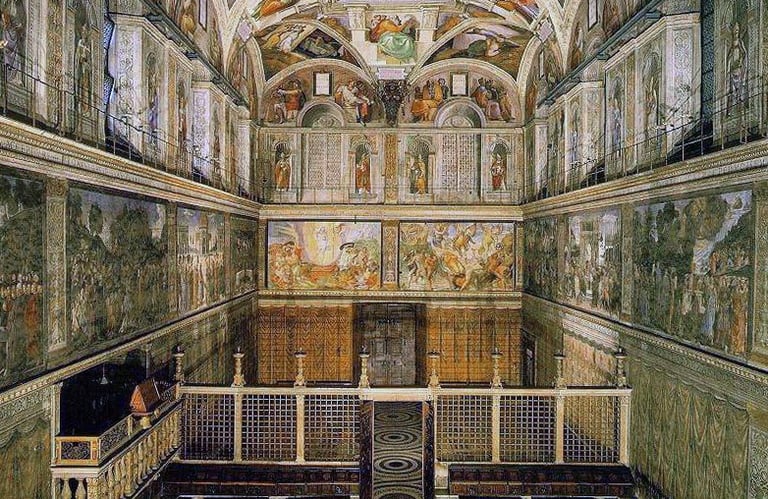

So, yes, the first proper conclave was not in Rome but Viterbo, and not in the Sistine Chapel (which was about 200 years away from being built) but in the Palazzo dei Papi (Popes’ Palace). It was also not uncommon for popes in the Middle Ages to take residence in Viterbo whenever Rome became too unmanageable, a fact that gained Viterbo the nickname la città dei Papi (the city of popes).

Tedaldo Visconti, who became Pope Gregory X after he was elected at the end of this very lengthy first conclave, was determined to never let the pontifical election go on for so long, and in 1274 he issued a papal bull that would prevent that from happening. A papal bull is so-called not because of any bovine connection, but after the lead seal that is attached to it which resembles a bubble (bulla, in Latin). It is often referred to by its opening words, and Gregory’s bull was known as Ubi Periculum (Where danger).

Pope Gregory X