You may have encountered the term ‘Machiavellian’, often used to describe someone as cunning, scheming and unscrupulous. This label originates from Niccolò Machiavelli and the principles he outlined in The Prince (or, in the original Italian, Il Principe). It was written sometime after 1513 but not published until after his death in 1532. Frederick the Great of Prussia took great issue with Machiavelli’s text. So much so that he penned a rebuttal, 200 years later…

Mirrors for Princes is a genre of political writing which aims to communicate guidance to newly crowned or inexperienced monarchs, helping them navigate the complexities of ruling and managing affairs of war and governance. The most famous example of this genre is perhaps Niccolò Machiavelli’s The Prince. However, as Frederick the Great’s rebuttal Anti-Machiavel reveals, what a prince needs to know is up for debate. While these texts might be dubious as guides for prospective monarchs, they might help us learn something about differing ideas of morality and governance at their time of writing.

Machiavelli and The Prince

Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527) was a Florentine political thinker, administrator and diplomat in the service of the Florentine Republic who, despite today being well-known mainly for writing The Prince, was a rather prolific writer touching on subjects ranging from military strategy to history and political thought.

In 1494 the Florentines expelled their unpopular de facto ruler, Piero de’ Medici, and formed a republic under the guidance of a rather stern Dominican friar named Girolamo Savonarola. After his excommunication and execution in 1498 the republic was headed by Piero Soderini. Machiavelli was heavily involved in the administrative and diplomatic operations of the new republic and especially with the attempt to raise a citizens’ army (which never quite took off).

When the Spaniards invaded Italy and reinstalled the deposed Medici family as rulers of Florence, Machiavelli found himself in an uncomfortable position. He was sacked from his administrative position and later, after the Medici suspected he was involved in a conspiracy against them, he was arrested and tortured. Luckily for him, Giuliano de’ Medici was elected pope (and took the name Leo X) and shortly thereafter Machiavelli was pardoned and was allowed to retire to Percussina in the Tuscan countryside.

From this moment forward until his death Machiavelli tried to return to public life and spent his time corresponding with political figures and writing treatises, such as his Discourses on Livy (Discorsi sopra la prima deca di Tito Livio) and, indeed, The Prince.

The Prince was written as a political manual for new princes (that is, rulers who took over a territory but had no preexisting legitimacy), and offers some unorthodox approaches to statecraft.

The mirrors for princes (Specula principum) genre was nothing new – the idea of writing instructive political texts for new monarchs and other young members of royal households in this manner can be traced back to Plato and Aristotle.

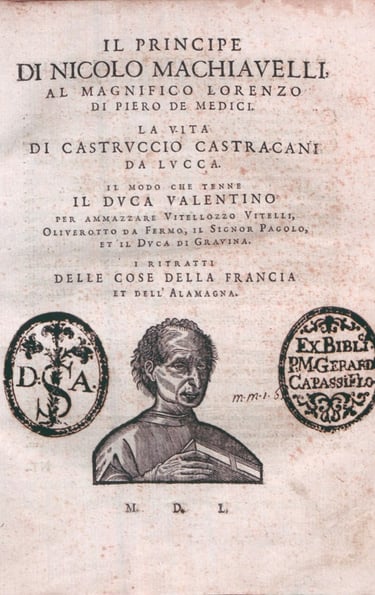

Machiavelli's The Prince in a 1550 edition.

The text begins with a dedication to Lorenzo de' Medici, Duke of Urbino who was the ruler of Florence and kept Machiavelli in exile in Sant'Andrea in Percussina. It outlines the qualities that a successful prince should cultivate, or at least appear to possess. For example, he lists some desirable and undesirable princely qualities. A prince is likely to be despised if he is “changeable, foolish, weak, mean and uncertain” and should try to act in ways which show “greatness, courage, seriousness and strength”.

He writes that a wise ruler should not shy away from conflict, as it is needed to create a good reputation. In fact, he goes so far as to suggest that it can be engineered: “a wise prince, when he has the opportunity ought to create some enemies against himself, so that, having crushed them, his reputation may rise higher.” How very Machiavellian!

Machiavelli stresses that a prince does not necessarily need to possess all of the qualities he describes, he notes that “it is very necessary to appear to have them […] A prince should appear merciful, faithful, kind, religious, upright, but should be flexible enough to make use of the opposite qualities when it is [necessary].”

Niccolò Machiavelli.

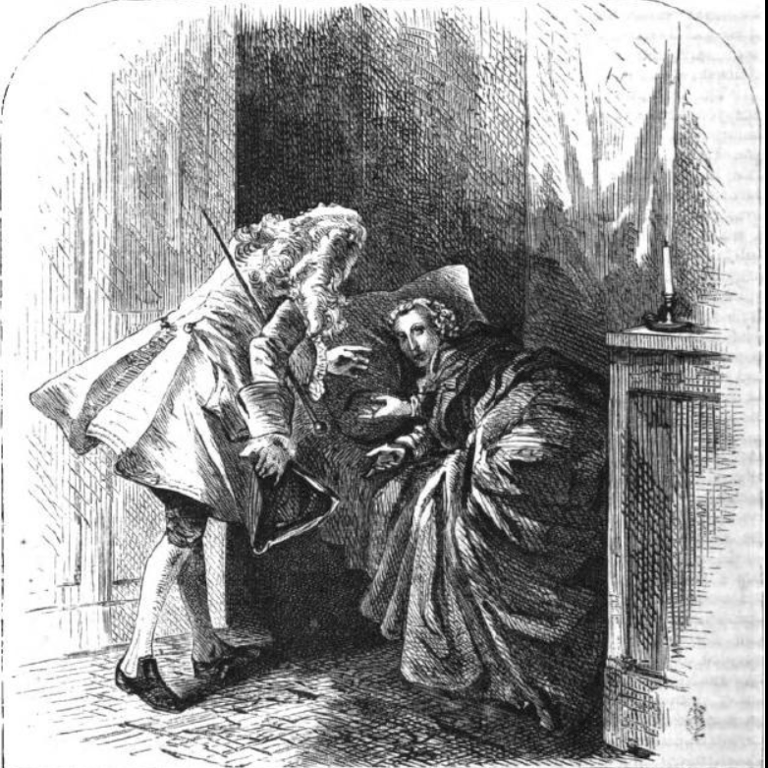

Frederick and Voltaire meeting for the first time.

Alongside his military achievements, Frederick was also a prolific writer. One of his works was the Anti-Machiavel. This text, written between 1738 and 1739, and revised by Enlightenment-era philosopher Voltaire, and published in 1740. Frederick’s text is a chapter-by-chapter rebuttal of Machiavelli, primarily on moral grounds .

His purpose is clear from the outset. He opens by stating “I will defend humanity against this monster which wants to destroy it; I dare to pit Reason and Justice against sophism and crime; and I put forward my reflections on Machiavel’s Prince, chapter by chapter, so that the antidote is immediately near the poison.” Cruel and calculating princes who act in their own self-interest, he argues, are detrimental to humanity.

It is perhaps worth stressing here the commitment Frederick the Great had to his visions of Enlightened thinking, a movement marked by an emphasis on reason and natural rights. Often remembered as an “enlightened absolutist” or an “enlightened despot”(a title also attributed to Catherine the Great of Russia)he presented himself as holding deeply the belief that the ruler is a servant of the state. His reign blended both authoritarian rule and Enlightenment reform. Embedded in the ideas of the “age of reason”, his policies included judicial reforms, religious tolerance of Catholic and Jewish people in an otherwise Lutheran Prussia, support for the arts, and certain freedoms of the press.

Frederick's Anti-Machiavel.

This context might go some way in explaining his response to Machiavelli. A poor ruler would bring devastation on the population:

“The floods which devastate regions, the fire of the lightning which reduces cities to ashes, the poison of the plague which afflicts provinces, are not as disastrous in the world as the dangerous morals and unrestrained passions of the kings: the celestial plagues last only for a time, they devastate only some regions, and these losses, though painful, are repaired. But the crimes of the kings are suffered, for a much longer time, by the whole people.”

The perceived cruelty of Machiavelli certainly struck a chord with Frederick. Particularly disturbing was Machiavelli’s suggestion that new princes should extinguish the bloodline of their defeated foes: “‘It is enough,’ this malicious man tells us, ‘to extinguish the line of the defeated Prince.’ Can one read this without quivering with horror and indignation?” Evidently, the brutality did not sit right with him. Perhaps it felt closer to home, given that he too was heir to the throne at the time of writing.

Perhaps most striking in his rebuttal is his response to Machiavellian notions of using fear to rule. Of this, Frederick writes “I advise that any king, whose sole method of their policy is securing obedience through fear, will reign over cowards and slaves. He will not be able to expect great actions of or from his subjects.”

So, what should a prince know?

The contrasting approaches to princely knowledge in Machiavelli and Frederick the Great represent how different forms of action and knowledge are valued at different points in time. Machiavelli’s The Prince reflects a pragmatic yet ruthless guide to power, while Frederick’s Anti-Machiavel demonstrates enlightenment ideas of civic duty and rational governance.

For a contemporary prince, these works are perhaps less significant for the literal advice they offer to would-be rulers, and more meaningful as mirrors reflecting the intellectual and moral climates of their respective times.

Sources

Anti-Machiavel: or, an examination of Machiavel's Prince. With notes historical and political. Published by Mr. de Voltaire. Translated from the French. 1741.

*Note that translations from this edition have been altered slightly.

Machiavelli, The Prince, trans. Harvey C. Mansfield

https://archive.org/details/machiavelli-the-prince-uo-c_202208