What is the history of knowledge?

Scilicet is a blog dedicated to the history of knowledge. In the broadest terms, we’re interested in what people in the past knew, what it meant to know things, and what we as historians can learn about that knowledge.

In one sense, this is a long-standing enterprise. Historians have always taken interest in different systems of knowledge and belief that have existed over millennia. There are histories of great thinkers from Plato to Einstein, and on different branches of knowledge, whether science and mathematics, magic and folk medicine, the skills and know-how of artists and tradespeople, or just about anything else.

But in another sense, the history of knowledge as an area of study is something quite new. It has emerged only in recent years, building on work in similar fields such as intellectual history, the history of science, or the sociology of knowledge, as researchers have increasingly recognised that what ‘knowledge’ meant was often very different to people in other times and places.

Traditional studies of past knowledge were oriented largely around modern, Western understandings of science and philosophy. But the last decades have seen a concerted effort by scholars to adopt a more global and comparative approach, recognising that the vastly different ways humans extract meaning from the world are all forms of ‘knowledge’, and that there’s much to gain by bringing these sometimes disparate mental worlds into conversation.

History is a discipline of context. It’s about relativising and historicising concepts that might seem uncomplicated or unchanging and realising that nothing we know about the world is certain. Just as we may recognise that individuals in the past believed things now regarded as fanciful, people in the future will doubtless think the same of us.

Ours is a world of institutions and experts, people with long series of letters after their names, ‘influencers’ in pulpits and on social media platforms, and news both factual and fake, each claiming to tell you what is ‘right’. Putting these claims to knowledge in their historical context and understanding their contingency is not to say whether they’re right or wrong per se, but rather to show that understanding how history has shaped the knowledge of today can help us better understand who we should listen to.

In that case, the history of knowledge needs to be one that examines different forms and systems of knowledge from different times and places. To fully understand what ‘knowledge’ looked like in the past in all its diversity, we need to consider people of all stripes: not just western scientists in laboratories but ordinary people from different countries and continents, those of different genders, and varying social, linguistic and ethnic backgrounds.

If we can recognise the value in all these people’s knowledge, and make sense of why some forms of know-how have been valued above others, then we’re well on the way to better understanding the fundamental ways in which knowledge has shaped, and will continue to shape, the world we inhabit.

In our own peculiar and modest way, the stories you’ll find on this blog – of melons (allegedly) killing popes; of people’s attitudes towards minorities or how they remembered the past; of now-discredited medical practices or obsolete measurement systems; of animals, jokes, gossip, and folk sayings; and the everyday lives of ordinary people – these are our way of pursuing a history of knowledge.

Feel free to explore the site and find posts that interest you. Or, if you want to learn more about the history of knowledge, read on below for some of the key themes you’ll find on this blog. And if you still want to know more, you’ll find a reading list at the end of this post.

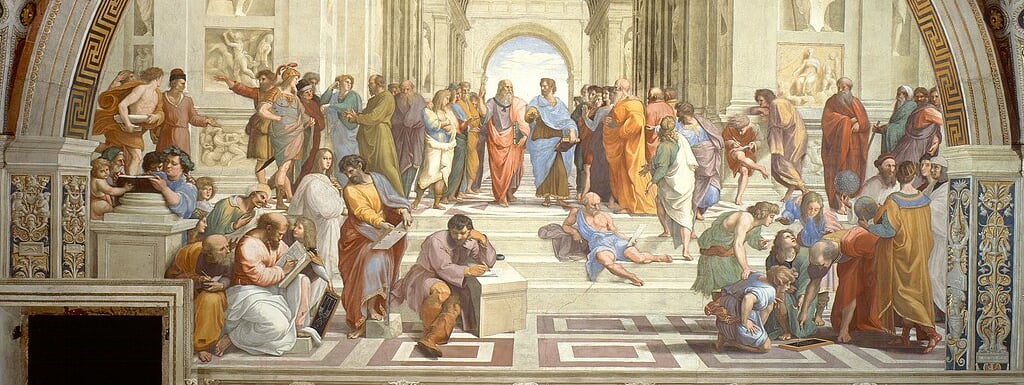

The School of Athens by Raphael (1511) showing a variety of very clever people.

What is there to know? (or, on ontology and epistemology)

One of the big questions in philosophy is ‘what is there?’. Philosophers from the time of Plato (fifth century BCE) up to the present day have tried to figure out what exists in the world, a study which they call ontology (or the study of being). Having explored this question and come up with various answers (some more outlandish than others) philosophers found themselves asking another important question: ‘what can we know about what exists?’ The field of study that emerged from this line of inquiry is called epistemology (the study of knowledge), and this is where historians’ interest is finally piqued.

As people whose main interest is understanding the past, all historians have to ask themselves to what extent we can know the past, what information and sources we can trust, and to what extent: how much we can be sure of anything that we read in our sources? These are all very difficult questions to answer and despite studying the past uninterruptedly for at least two and a half millennia, we still haven’t arrived at a clear enough answer that we all agree on as a discipline.

There are, however, a few guidelines that have become widely accepted by modern historians, for example, that we must try to avoid anachronisms. Anachronism (from Greek ‘ana’, against, and ‘chronos’, time) is when a historian introduces a concept, interpretation, terminology etc. which does not belong in the period which they study (e.g., feminism in the Roman Empire). Anachronistic readings of history can distort our understanding of the past and therefore it is agreed that we should try to understand the past and the knowledge of past people on their own terms. Even though an argument can be made that eliminating anachronism entirely is impossible (since, by definition, we live and write in, and are informed by the present), we still need to be always vigilant.

Another thing historians often think about is how much we simply cannot know about the past. Some knowledge people had which was not documented or that was documented and subsequently lost is simply unrecoverable. In fact, there is far more knowledge that is lost to the ages than things that were handed down to us, and even then, historians are aware that just because something is written down does not make it necessarily true. Every source has its own agenda and this requires us to be critical of our sources. Different historians have differing opinions on how well we may bridge this epistemological gap (or, how well can we reconstruct the past and how contemporary people understood their world even without all the things that we will never know). While there is no definitive answer to this question, it is important to keep thinking about it.

Knowledge systems: Science and scientists

The growing critical attention paid to the category of knowledge has seen historians refer increasingly to knowledge as the product of ‘systems’ – interconnected webs of individuals, communities, institutions, the ideas that spread between these groups, and the way they’re communicated. It’s within these ‘knowledge systems’ that existing know-how is evaluated and new knowledge produced. Examining past knowledge systems therefore helps us understand how people in the past and the present day have come to understand beliefs they hold to be ‘knowledge’ or ‘truth’.

Modern, Western science (from Latin scire - to know), in the form that has emerged in the last 400 years or so, is a telling example of such a knowledge system. Today, scientific knowledge, perhaps more than most forms, is held as a bastion of truth, with dedicated experts who train for many years and take advantage of the latest technology to produce, through verifiable and peer-examined experimentation, reliable knowledge about the natural world.

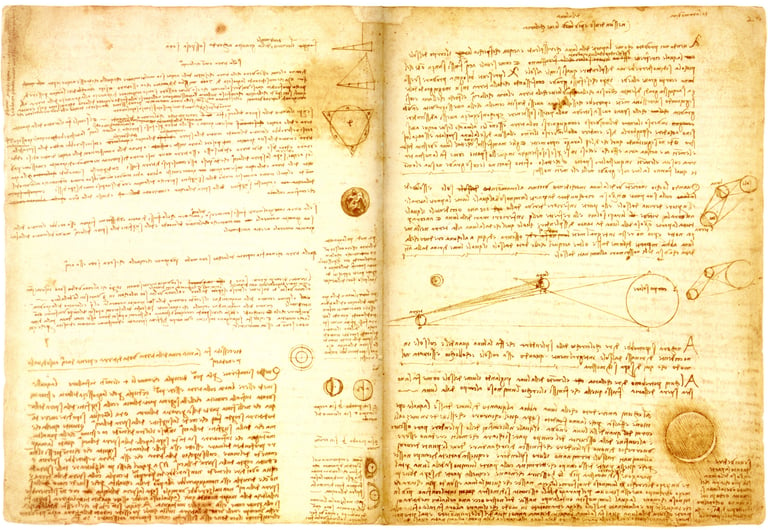

Scientific drawings by Leonardo da Vinci (1506–1510).

Joseph Wright, An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump (1768). From the later 17th century, air pumps were commonly used to conduct experiments on the properties of air.

Knowledge and belief

If you’ve read this far, you may be starting to question whether it’s really possible to ‘know’ anything. Isn’t everything we think just a form of belief or the product of an arbitrary system? Deeply philosophical questions such as these are difficult to answer, but once again, examining past forms of knowledge can help inform our judgement.

It’s often easy to tell the assumptions of historians about what is and is not ‘true’ based on what understandings of the world are relegated to the realm of ‘belief’. On this blog you’ll encounter posts about astrology, discredited ideas about medicine, conjuring tricks and magical charms and various other ideas people had which surely few today would take seriously, and are therefore described as ‘beliefs’.

But it’s rarely that simple. Practices that we might now consider to be ‘magical’ (e.g., alchemy or astrology), have been at the cutting edge of inquiry about the natural world for all but the last few centuries. Famously, Isaac Newton, who is in many ways an archetypical figure for the kind of modern, mathematical and experimental science advocated by bodies such as the Royal Society, was privately very interested in alchemy (the notion that base metals could be turned into gold through chemical processes).

One of the reasons why disregarding these ‘beliefs’ is problematic (apart from the disrespect for past peoples and their knowledge) is that the false dichotomy between the silly superstitions of the past and ‘proper’ modern knowledge keeps us from noticing our own ‘beliefs’.

The thing that makes modern science so useful is that it’s not dogmatic; all our best knowledge and theories are just the best that we’ve got so far, and once better information or explanations come along we must be willing to change our views and opinions. Remaining respectful of past knowledge and beliefs should therefore keep us realistic about the current state of our knowledge along with the understanding that it is bound to change. That is the scientific way after all.

An astrological drawing from Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (15th century).

Communication

A vital aspect of the knowledge ‘systems’ outlined above is the modes and networks of communication through which knowledge is transmitted. Without means to communicate our ideas, knowledge would remain in the domain of individual thought, and we might even go so far as to say that knowledge is defined by the way it’s communicated. This was certainly the stance taken by the influential historian of science Jim Secord, who argued for the necessity of thinking of science as a form of communicative action, taking account of when, how and between whom knowledge of the natural world was shared. It’s therefore essential to understand the ways people in the past communicated with each other, because those methods of communication have deeply influenced the knowledge of individuals past and present.

Two fundamental developments since the Middle Ages have been the rise of literacy and the advent of moveable-type printing. According to a popular narrative, in medieval times very few people beyond the most wealthy and well-educated could read and fewer still could write and books were rare and expensive items written by hand. Only a few centuries later, the ability to read and write was a normal part of daily life for most people in many parts of Europe, as were encounters with printed books that could be mass produced in thousands of copies. The reality is of course somewhat more complicated than that, as we tried to demonstrate here.

The definition of literacy can and should be questioned and more attention should be paid to oral transmission of knowledge. Indeed, the capacity of people from oral cultures to memorise by heart was much more impressive than our own (just think of how many phone numbers we used to know by heart before smartphones, and if you’re under 35 - ask your parents). It is certainly possible to overstate the importance of these transformations, but as several of our posts demonstrate, evolving modes of communication have played a central role in the history of knowledge.

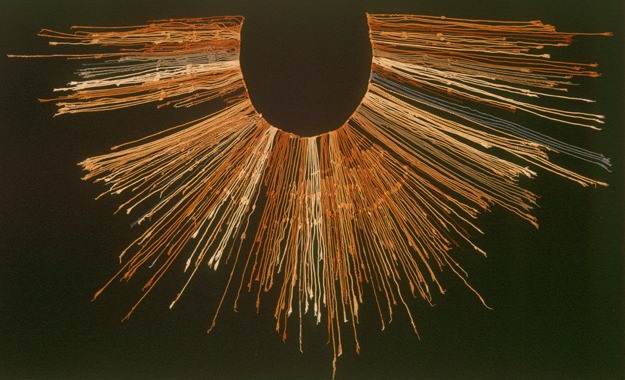

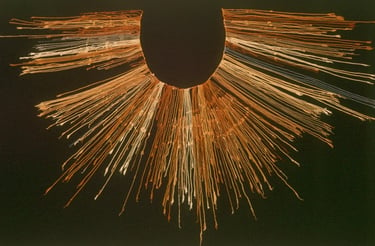

Quipus, traditional in parts of South America, were a form of counting and recordkeeping quite different to Western pen-and-paper methods.

The spread of printing and literacy certainly increased access to knowledge among the wider population on paper (pardon the pun!), but we should also be aware of the ways that these developments have marginalised certain groups. In the past, as today, cultivating literacy depended on conducive cultural environments and factors such as access to books and education, all of which are socially restrictive.

In the case of books too, it’s easy to assume that their production increased access to knowledge and aided its development. This was the line taken in Elizabeth Eisenstein’s controversial The Printing Press as an Agent of Change (1979), which argued that the invention of moveable-type printing was crucial to the emergence of modern science as it allowed knowledge to be ‘fixed’ in texts, giving them authority. More recent studies like Adrian Johns’s The Nature of the Book (1998) have painted a more complex picture, showing how the knowledge conveyed in printed books was often imperfect and anything but trustworthy. Powerful gentleman-scientists used these books as a medium for scientific communication to establish the authority of their knowledge, even though its credibility was sometimes questionable. In this sense, printing may be considered integral to the emergence of knowledge systems like those considered above.

Book printing in the 16th century (1520).

Not knowing

If historians were relative latecomers in studying the category of ‘knowledge’, it is still only more recently that their critical attention has fallen on the other side of the coin: ignorance. Ignorance comes in several forms and has a complicated relationship with knowledge. Forms of ignorance might include not knowing something, but also knowing you don’t know something; feigning to not know something; even not knowing that you do know something! Moreover, producing new forms of knowledge inevitably produces new forms of ignorance by creating stuff that other people don’t know yet.

We tend to think of ignorance as a bad thing, an absence of knowledge that must be remedied. But, as Peter Burke has recently observed, ignorance can sometimes be useful, for example if it allows us to prioritise some forms of knowledge over others. Ignorance can also be a source of power: think, for example, of some politicians’ and think tanks’ efforts to gain support by denying evidence of climate change. Authorities throughout history have also sought to limit access to knowledge for similar ends, as in the case of the sixth-century Decretum Gelasianum, which fixed what books were part of the Bible and suppressed other texts that Catholics deemed heretical. The infamous Index Librorum Prohibitorum (Index of Banned Books), which appeared in the sixteenth century (abolished in 1966) tried to ban all manner of authors that the church did not approve of.

Even if we accept that ignorance might generally be a bad thing, it is certainly a useful way of thinking about history. Historians are increasingly aware that ignorance has played important social functions in the past (we wrote about it here and here). Many of history’s greatest minds (e.g. Socrates, Montaigne) have celebrated their ignorance, all too aware of what they don’t yet understand.

Ignorance is also something that can be created by people who wish to protect or ‘gate-keep’ their knowledge by excluding people from accessing knowledge freely. Craft guilds – institutions which have existed since the Middle Ages to organise and protect trade through controlled apprenticeships and licenses for practice – may be viewed as another example of this.

Another example of gate-keeping knowledge is found in mysticism. Mystics were sometimes quite ‘out there’ in their interpretations of scripture and theology and people of the religious establishment often feared that if the uninitiated got access to such knowledge it may lead to ‘heresy’ and even social upheaval (the Cathars of the 13th century and Anabaptists takeover of Münster in the 16th century are just two examples where radical theology had serious consequences in the real world). This sort of knowledge was therefore kept esoteric, only accessible to experts who won’t misinterpret it.

What's on Scilicet?

If you made it this far, you now know how wide and dynamic the history of knowledge can be as a field. What we aim to offer here is our own take on it. While geographically our own expertise is focused mostly on Western Europe between the late Middle Ages and the eighteenth century, we are interested in many forms of traditional and less traditional knowledge. We try to write about everything from the pure sciences and philosophy to astrology and magic; knowledge practiced by the most revered and learned in society as well as the ignored and marginalised. All of them deserve a blog post!

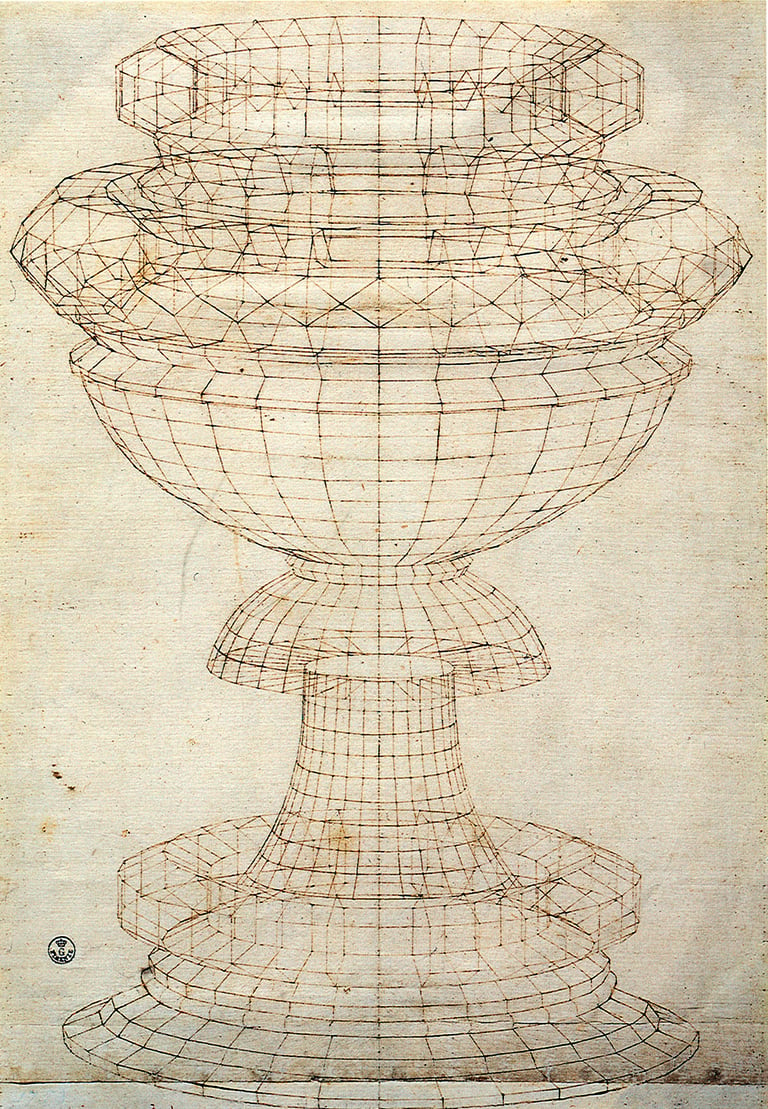

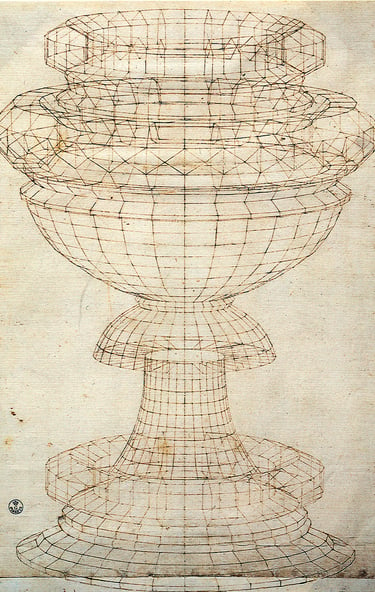

Paolo Ucello’s perspective study of a chalice (1430).

Bibliography and Reading list

If you’re interested in reading more about the history of knowledge, we’ve put together a reading list.

The Lund Centre for the History of Knowledge (LUCK) also has some useful sources.

James Beattie and Ruth A. Morgan, ‘From history of science to history of knowledge? Themes and perspectives in colonial Australasia’, History Compass, 19 (2021), pp. 1–10.

Peter Burke, A Social History of Knowledge: from Gutenberg to Diderot (Cambridge: Polity, 2000).

Peter Burke, A Social History of Knowledge II: from the Encyclopédie to Wikipedia (Cambridge: Polity, 2012).

Peter Burke, Ignorance: a Global History (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2023).

Elizabeth Eisenstein, The Printing Press as an Agent of Change (2 vols., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979).

Lorraine Daston, ‘The history of science and the history of knowledge’, Know, 1 (2017).

Christian Joas, Fabian Krämer and Kärin Nickelsen, ‘Introduction: history of science or history of knowledge?’, Berichte zur Wissenschaftsgeschichte, special issue: history of science or history of knowledge, 42 (2019), pp. 117–25.

Adrian Johns, The Nature of the Book: Print and Knowledge in the Making (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1998).

Johan Östling, David Larsson Heidenblad (eds.), Forms of Knowledge: Developing the History of Knowledge (Lund: Nordic Academic Press, 2020).

Irene van Renswoude, ‘What (not) to read in times of crisis: response to the first index of banned books (c. 500 to c. 1100)’ in Renate Dürr (ed.), Threatened Knowledge: Practices of Knowing and Ignoring from the Middle Ages to the Twentieth Century (London: Routledge, 2021), pp. 25–51.

Steven Shapin, A Social History of Truth: Civility and Science in Seventeenth-Century England (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1994).

James A. Secord, ‘Knowledge in Transit’, Isis, 95 (2004), pp. 654–72.

E. C. Spary, Eating the Enlightenment: Food and the Sciences in Paris, 1670–1760 (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2012).

Lukas M. Verburgt and Peter Burke, ‘Introduction: histories of ignorance’, Journal for the History of Knowledge, 2 (2021), pp. 1–12.