Let’s look at this altarpiece from the Museo civico d’arte antica in the city hall of Pistoia.

Annunciation scene and two saints, Museo civico d'are antica, Pistoia.

The work

In this triptych, or work made of three panels, we can see St Nicolas on the left in his guise as the bishop of Myra, before he was promoted to the position of Father Christmas. On the right there is St Julian the Hospitaller, and in the middle, an annunciation scene. Kneeling between the angel Gabriel and the Virgin Mary is the man who commissioned the work, Gabriello Panciatichi, a member of one of the most important families from Pistoia. The triptych was originally kept in the Franciscan convent in Giaccherino, just west of Pistoia.

It is a very competently made work of art in the late Gothic style; the central panel was painted by Mariotto di Nardo and the other two by Rossello di Jacopo Franchi in the early fifteenth century. But the quality of the work is not what drew my attention to it when I first saw it in 2018 – it was the inscription below. Let’s have a closer look.

The Inscription

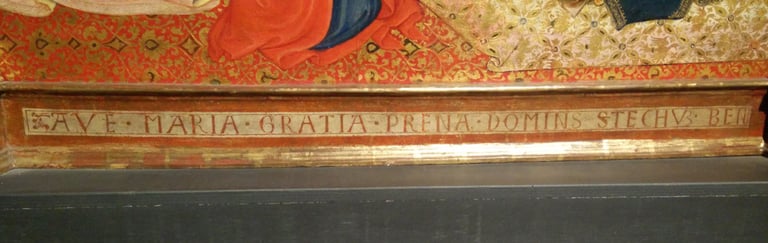

The inscription underneath the main panel reads:

‘Ave Maria gratia prena Domins stechum ben’

This is, of course, the first line of the Ave Maria or Hail Mary prayer, but it looks a bit odd…

Here is what it’s supposed to look like (I highlighted the differences in spelling):

Ave Maria gratia plena Dominus tecum ben[edicta tu in mulieribus…]

Translation: Hail Mary, full of grace, The Lord is with thee. Ble[ssed art thou amongst women…]

The person who wrote these words at the bottom of the panel was probably not one of the artists, Mariotto or Rossello, who painted the panels. It was possibly a third artist from their workshops who was tasked with making the elaborate gilded wooden frame around the painted panels. He probably knew his letters, but only just. What can be said about him with a bit more certainty is that he must have heard the Ave Maria recited in Latin often enough to confidently write it down how it sounded to him.

Since the consonants ‘L’ and ‘R’ can sometimes sound like each other, it is no wonder that he wrote ‘prena’ instead of ‘plena’. This type of mix-up was very common in the Middle Ages, when idiosyncratic spelling was the norm rather than an oddity – sometimes you’d see different spelling of the same word or name on the same page! Apart from that, when ‘Dominus tecum’ is said quickly it may be a bit difficult to tell where one word ends and another begins, so we get ‘Domins stechum’. Adding an ‘H’ after a ‘C’ to indicate that it’s a hard ‘C’ (even if there is no ‘E’ or ‘I’ after it to suggest otherwise) was also quite usual in medieval Latin orthography, especially in Tuscan sources.

The problem here, as any Latin teacher would tell you, is that this spelling suggests that the writer did not recognise that ‘Dominus’ is a noun in the second declension that in the nominative case ends with -us, nor did he seem to recognise that ‘tecum’ is a common way of writing the words ‘cum’ (with) and ‘te’ (you) and it does not require an ‘S’ at the beginning.

The Panciatichi family coat of arms

What do we mean by literacy?

So, what does it say about this artist’s literacy? If we asked him to decline all the nouns in that sentence he wrote, how well would he fare? Could he understand the Latin of the Bible, or of St Augustine or Cicero? And does any of it even matter? He was, after all, an artisan who (we can assume) had some capacity of reading and writing in the vernacular. This would have allowed him to manage his affairs like many other skilled workers at the time. So, why should we even measure literacy only in relation to his knowledge of Latin?

Having good Latin was important for scholars, lawyers, priests, administrators, diplomats, physicians and a few other professions. But most other people had different jobs and did not need to use Latin to the same extent. Many of them could, however, read and write in their own dialects of the widely spoken language, which served them well enough in their daily lives.

A language is a useful thing and when we think of linguistic proficiency we should consider the different ways in which it was intended to be used and how well these uses were met. A classicist with excellent Greek and Latin might find that they struggle to follow a biology textbook, even though it uses plenty of terminology derived from Greek and Latin. So despite their classical literacy, are they fully literate when confronted with a scientific text?

It would also be right to point out that it seems that no one had asked our painter to redo this inscription and spell the words correctly this time. Both Gabriello Panciatichi and the Franciscan friars of Giaccherino must have deemed it acceptable even though they were very likely to have noticed the unusual spelling of the Latin. This type of artwork was usually placed behind an altar and most people would have only seen it from afar. Moreover, it was the painted figures who were the objects of viewers’ devotion and interest. No one would have looked too closely at such an inscription (apart from incorrigible pedants such as myself).

There are no definitive answers to any of these questions raised here, but the one argument I will make is that it is always good to question assertions about historical rates of literacy and to focus more on its uses and social implications, like here.

Palazzo del Comune, Pistoia, where you can see the triptych.

Sources

Giacomo Guazzini, Elena Testaferrata, Valentina Baffi, Due pittori tardogotici fiorentini per Pistoia: Mariotto di Nardo e Rossello di Jacopo Franchi (Pistoia, 2015).

A special thanks goes to Dana Weaver for her help with this post!