Truth is one of those concepts that underpins any human society I could think of. Our ability to tell what’s real and what’s not helps us understand our world, acquire knowledge and maintain social bonds. If we know someone is telling us the truth, we are more likely to trust them and vice versa. One of those places where the truth is particularly important is the courtroom. Often much is at stake including people’s lives and freedom, so ascertaining the truth is a priority, but how did they do it in the past?

Before DNA tests, fingerprints, security cameras, and other modern methods of extracting forensic evidence, there were various types of admissible evidence in pre-modern courts. The best you could hope for was an eyewitness, or better yet, make it two, so that their testimony could be properly corroborated. Written documents could also be extremely valuable in certain cases - contracts and disputes over privileges and land ownership come to mind.

But what if the court did not have anything as solid as that? This is when relying on fama became necessary. Fama, a fundamental concept in medieval legal thinking, is tricky to translate. It can mean reputation, but also hearsay or gossip. The phrase that most captures its meaning, I would suggest, is the word on the street – what people are thinking and saying about a person or about something that happened.

Nowadays, we tend to scoff at the idea of citing hearsay in a courtroom as proper evidence, but sometimes there is no choice but to rely on fama and modern courts still allow it today (albeit under certain restrictions). The problem here is, to put it rather pompously, that there is an epistemological gap (that is, a gap in what can be known) that prevents us from knowing with complete certainty what is true and what isn’t, so we must trust our best available educated guess and hope we get it right. This was sometimes more complicated than it sounds…

The case against Lazzarina

One fascinating case from fourteenth-century Bologna tells us about a local woman called Lazzarina, who was accused in January 1324 of being an ‘infamous woman and a notorious keeper of prostitutes as well as a brothel proprietor’.*

This was a serious accusation since, like in many other cities at that time, making profit from sex work (meretricium),** was illegal in certain parts of Bologna (although it remained commonplace). But how could the court establish her guilt or innocence?

The judge, a notary from the Fango Office named Giacomo, heard five testimonies from neighbours as well as from Lazzarina herself in an attempt to establish the facts. Everyone who testified in this case claimed that their evidence was publica vox et fama or common knowledge on the street, but as you might have guessed, some of the testimonies do not necessarily agree with each other.

Certain facts in this case were agreed on by all parties, namely, that Lazzarina lived in a particular house in the parish of San Salvatore in Bologna, and that men and women were seen coming in and out of that house. Now, this information can be interpreted in a number of ways, and our witnesses in this case suggested two interpretations in particular.

* ‘…infamam et famossam et retentricem melletricum et hellenonum’. A more usual spelling would be ‘retentricem meretricum et lenonem’, more on medieval orthography can be found in our previous post.

** From meritum – merit or value.

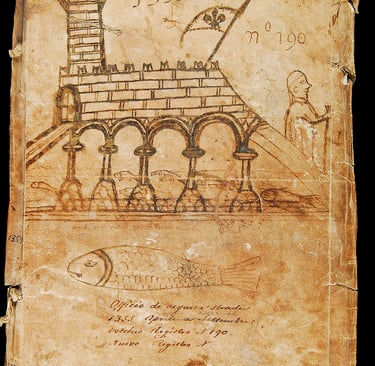

Cover of one of the registers from the Fango Office, the court that tried Lazzarina, from 1355.

A den of inequities

Four of our witnesses claimed that Lazzarina was an ‘infamous woman’ and a brothel keeper, and that the men and women coming in and out of that house were sex workers and their customers. Moreover, everyone knew about all this (de predictis omnibus est publica vox et fama).

Serious accusations indeed. The fact that they were made by four men of fairly high social status might not come as a huge surprise. Three of them were introduced by the title magister (master), and we know that one of them was a doctor grammatice (doctor of grammar, most likely at the famous University of Bologna). The other two might also have been teaching at the university, or perhaps held senior positions in Bologna’s guilds which were at the time centres of political power. This matters because the way to assess the level of trustworthiness of a person was often by their social standing and the company that they kept, as well as their personal fama. A pomposity of professors was considered more trustworthy than someone from the bottom rungs of the social ladder, and – rightly or wrongly – this is still how our society often judges people.

So Lazzarina was in big trouble, but this was by no means a done deal…

A trattoria

One of the most gratifying things about reading medieval trial records is seeing how resourceful so-called ‘ordinary’ people were. In many cases they understood the law and how to manoeuvre it just as well as any seasoned lawyer. Lazzarina, who was accused of being a brothel keeper, presented the court with an alternative explanation to the facts that everyone agreed on: that there was a house in the parish of San Salvatore and people were coming in and out of it.

I bring her defence as recorded by the judge here in translation:

Lazzarina from the parish of San Salvatore in Porta Nova appeared before me, the fango notary… and interrogated about the aforementioned [allegations]… she responded and said that she was staying in that house… during the day in order to sell food which she makes in that house. And she denied that everything and anything else contained in the investigation was true.

So not a brothel but an eatery. The men and women coming in and out of that house were not necessarily of dubious morality and propriety, but just a bit peckish. It was a clever defence and luckily for her, another neighbour was happy to confirm her version. That person, similarly to Lazzarina, seems to have been from modest social standings - he had no honorific or family name, which was reserved for posh people in the middle ages. Francesco, who was from the same neighbourhood of San Salvatore, confirmed that Lazzarina stayed in that house and sold food that she made, but he also said that he saw prostitutes (meletrices) and other people (alia gentes) coming in and out of that house, and that all of that was common knowledge.

Frustratingly, we do not know the outcome of Lazzarina’s trial and whether or not the court found her explanation convincing, as this information was omitted from the register. But there are reasons to assume that the court sided with the accusers who were likely considered more trustworthy due to their social status (and were also more numerous). Despite the temptation, we should not try to determine the truth in Lazzarina’s case, no matter how much we may want to stick by a marginalised woman against her higher-status accusers. We just don’t have enough details to ascertain all the facts.

The more interesting lesson to draw from this case which applies more generally to medieval and early modern Europe is about the social nature of truth and the mechanisms that can generate it. If people say something is true and insist on it, then unless it can be disproven, it is – for all intents and purposes – true. Therefore, the best chance of inhabitants of the medieval city who found themselves at odds with the authorities or each other was to stand by their peers. They would often share resources, use their collective ability to generate fama, protect each other’s reputation and defend each other in court and on the street. In pre-modern societies where fama and trust were key, social cohesion was everything.

Sources

Archivio di Stato di Bologna, Comune, Curia del Podestà, Ufficio Acque, Strade e Fango, b. 17, 1324 I, ff. 10r-11r.

Thelma S Fenster and Daniel Lord Smail, eds., Fama: The Politics of Talk and Reputation in Medieval Europe (Ithaca, NY, 2003).

Ian Forrest, Trustworthy Men: How Inequality and Faith Made the Medieval Church (Princeton, NJ, 2018).