In 1664 a new and exciting book appeared in London’s bookshops. In a compact text of 170 pages, it discussed everything from market prices to the death of kings, weather forecasts to the rules of arithmetic. Its name: A Book of Knowledge.

This work is little discussed today, and less still is known about its mysterious author, Samuel Strangehopes. But in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries it seems to have been a popular title, reprinted at least ten times.

A general guide to understanding the natural world, it was in fact three books in one: an introduction to reading signs of the zodiac, a medical manual with lessons on basic arithmetic, and an agricultural textbook. What united these topics was astrology, the belief that events on earth were controlled by heavenly bodies. Understanding the way that astrology connected these three ostensibly different subjects offers a valuable lesson on the vitality of pre-modern knowledge systems.

‘For the Capacities of the unlearned’?

One indication of the significance of A Book of Knowledge is how widely it seems to have been read. As its preface indicated, this was a book aimed at the ranks of society who weren’t likely to receive extensive education. But whether it actually met this intended audience is less certain. In the absence of sources demonstrating its readership, clues in the book’s material characteristics are the next best thing.

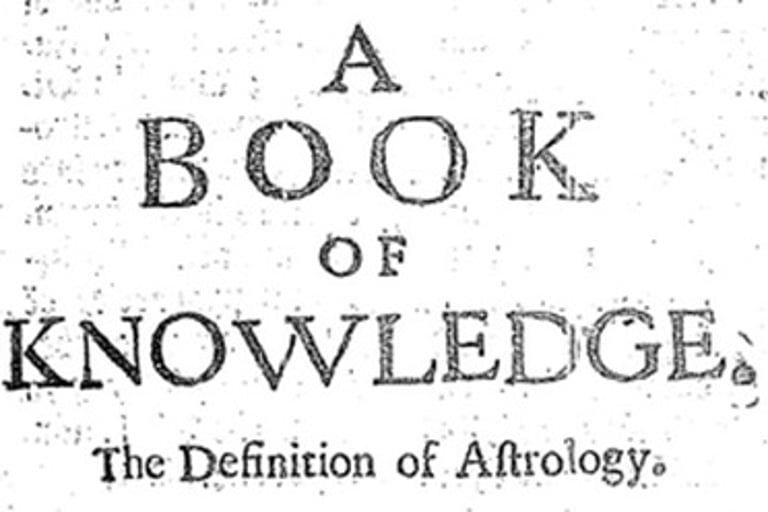

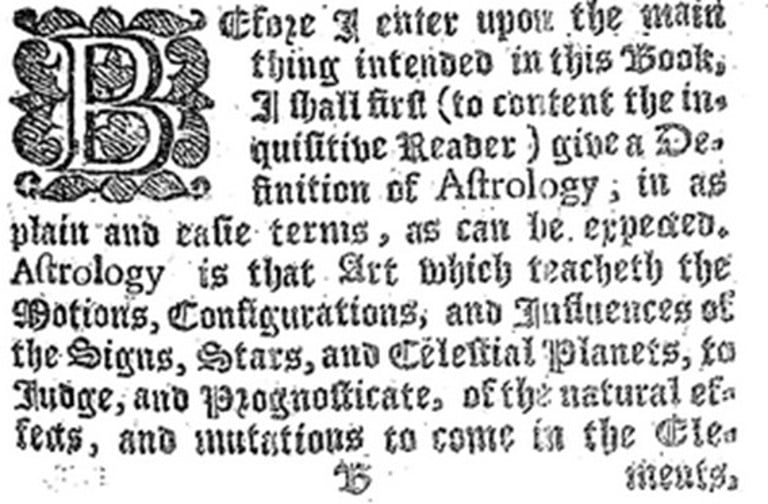

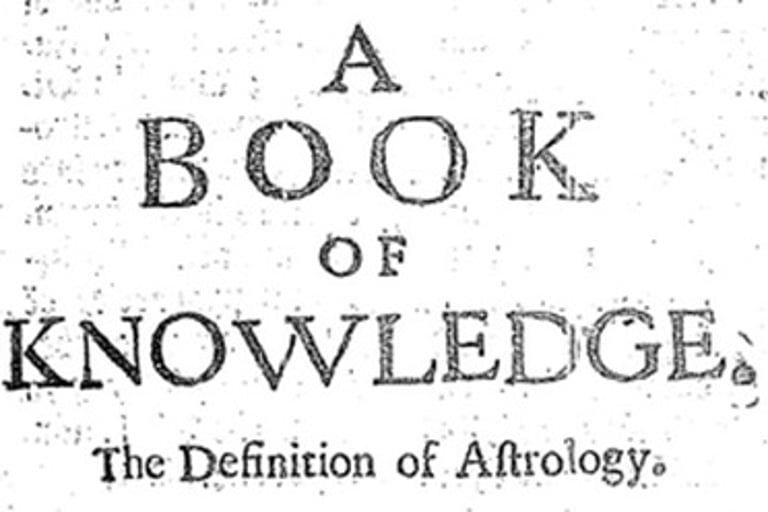

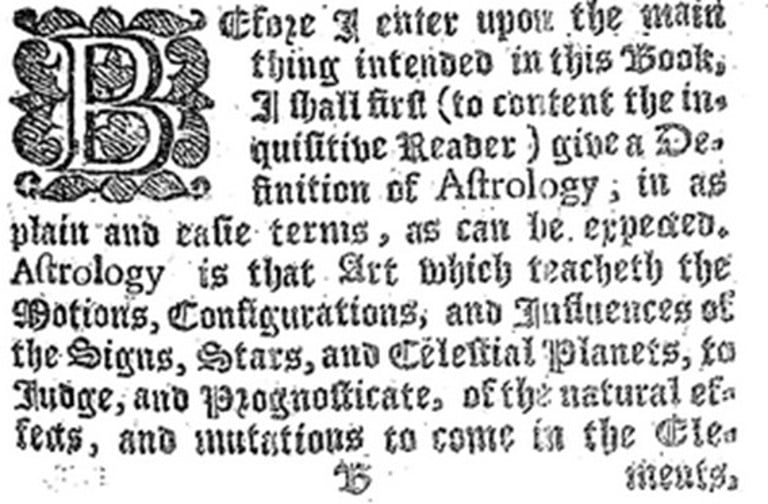

One of these is the font. Although the title page of A Book of Knowledge is printed in a classic Roman type, the ancestor of our own Times New Roman, the substantive text appears in another font known as blackletter. And herein lies the clue: blackletter was used especially in works aimed +at mass audiences as many in England found it easier to read. It was commonplace in sixteenth-century texts in an era of lower literacy, but its presence in a book produced in the later seventeenth century is suggestive of its wide intended audience.

Left: the roman type title page. Right: substantive text in blackletter font.

Another indicator of the book’s reach is that it was sold at a shop called the Three Bibles on London Bridge, which was one of London’s key vendors of cheap and popular titles. Other books sold here included titles we’ve discussed previously, such as the hugely popular maths textbook Cocker’s Arithmetick, and a manual for aspiring servants called The Compleat Servant-Maid.

A Book of Knowledge therefore became a common feature on the roster of so-called ‘chapmen’s books’: short, cheap booklets that were sold to mass audiences by travelling sellers known as chapmen. Tellingly, it was still among the titles listed in one chapbook catalogue printed in London almost a century later in 1760. As late as 1793, an American bookseller’s catalogue listed it among the chapbooks, rather than in its ‘Arts & sciences’ section or that on medical texts.

One final gauge of its popularity is the small number of copies that survive today. A paradox known to any historian of early printing is that the most popular books of the past exist today in the smallest numbers. These were the books that were heavily used until they fell apart, rather than remaining in good condition as they gathered dust on library shelves. With only a handful of copies known to survive, A Book of Knowledge certainly falls into the former category. The edition of 1684, for example, survives in only a single known copy. It’s quite likely, then, that there were more editions of this book that are now simply lost.

An all-encompassing system?

If this book was so popular, what did it have to offer? The answer lies in the link between astrology, medicine and farming that formed the basis of the text. Astrology was the glue that bound these subjects together, offering an all-encompassing knowledge system to explain natural phenomena.

Agriculture and medicine were just some of the things thought to be controlled by celestial movements. If you wanted to know whether you’d end up rich or poor, where to locate lost possessions, or decide whether to embark upon risky travel, astrology had answers. It may not always have forecasted events correctly, but it offered a way of explaining a natural world otherwise shrouded in uncertainty.

Astrology was an extensive and diverse corpus of knowledge accessible on multiple levels. Many of its lessons possessed an authority inherited from key thinkers of the ancient world like Ptolemy and Aristotle, and it was a subject of genuine intellectual enquiry among early modern scholars such as John Dee. Perhaps the appeal of A Book of Knowledge was that it offered an easy way into this vibrant intellectual universe.

John Dee was a sixteenth-century astrologer and mathematician who served as a scientific and medical adviser to Queen Elizabeth I

The work began by explaining the signs of the zodiac and characteristics associated with each. Astronomical information included the order of the planets and the lengths of their orbits. The Sun and moon were counted among the seven named planets, while Uranus, yet to be discovered, was not.

Predictions were based on factors such as the day of the week that New Year’s Day fell on. Monday meant an uncomfortable winter and temperate summer, and more alarmingly for some readers, ‘the death of Kings, Nobles, and great men… and a downfall of the Gentry’.

Then, of course, there was information that connected astrology to farming and medicine. It taught readers how to predict the weather based on the position of the planets in a given month. If, for example, the moon was clearly visible in the night sky three days before it was full, then weather would be fair, but if not, ‘it will Rain much before four daies’. Wind was controlled by the power of the sun. South winds were thought damaging to seeds, fruits and living creatures. If New Year’s Day fell on a Thursday, meat prices would rise due to high mortality among cattle.

When it came to medical advice, A Book of Knowledge told which parts of the body were affected by different star signs. Aries, for example, ‘ruleth the head, eyes, and ears, and the Diseases incident to them’. Back pain, for which you could blame Leo, could be eased with a medicine of cow dung fried in vinegar. For scurvy, the prescription was cloves boiled in rose water and ground to a paste to rubbed in the gums.

In matters such as childbearing, medical instruction morphed in more general life advice. It suggested nursing one’s child when the moon was at its closest to Venus, and to send them to school when it bypassed mercury.

The decline of magic

In A Book of Knowledge, then, we can see why astrology, farming and medicine were connected. This was a time when the universe and everything in it was understood in relation to a cosmic order. Lived reality was considered a reflection of a higher, divine plain of existence revealed by celestial bodies. Understanding anything about the world meant studying the cosmos (from the Greek word for order).

Yet such beliefs were in decline by the appearance of the last known edition of 1701.

When the book first appeared in the mid-seventeenth century, astrology was enjoying a moment of particular popularity. This was the heyday of the annual almanac, the small, cheap booklets that offered astrological predictions, and were printed in up to 400,000 copies a year – roughly one for every three households in England. Almanacs predicting violence and tumult had surged in the years of fear and uncertainty during the civil wars that plagued the British Isles in the mid-seventeenth century.

By the eighteenth century, however, astrology was losing some of its intellectual vitality. The fact that the book appeared in contemporary catalogues as a chapbook, rather than a medical or agricultural treatise, casts doubt on how seriously this knowledge was taken. Yet it also shows that people still found meaning in astrology’s teachings, as indeed some do today.

People took it seriously for good reasons. If everything from arithmetic to astrology, curing disease to planting orchards, could be encompassed in a single knowledge system summarised in one compact book aimed at a wide audience, it demonstrates that past knowledge systems had much to offer those they served.

The information contained in A Book of Knowledge wasn’t just miscellaneous folklore or collections of anecdotal superstitions. It was a fully fleshed out, systematic corpus of knowledge that gave meaning to natural phenomena for people at all levels of society.

It was one example of just how seriously astrology was taken that prompted Keith Thomas to write his ground-breaking study of early modern English popular belief, Religion and the Decline of Magic (1971), as he discusses in this clip. Fifty years on, accepting the knowledge of people in the past on their own terms remains central to the historian’s craft.

Sources

A Catalogue of Chapmens Books. Printed for Henry Woodgate and Samuel Brooks, at the Golden Ball, in Pater-noster-row (London, [1760?]).

Louise Hill Curth, English Almanacs, Astrology and Popular Medicine: 1550–1700 (Manchester, 2007)

Samuel Strangehopes, A Book of Knowledge (London, 1663 [i.e. 1664]).

W. P. Young’s catalogue of books, for sale, on the most reasonable terms, at Franklin’s Head, No. 43, Broad-Street, Charleston. June 1793 (Charleston, 1793).

Frontispiece of the 1679 edition.