Happy Guy Fawkes Day! This 5th November, if you happen to find yourself without access to a public fireworks display, fear not. As in so many of life’s big conundrums, early modern books have the answer.

Take, for example, Art’s Treasury of Rarities, a cheap book of magic tricks, arts and crafts, and household ‘life hacks’ printed in London and Glasgow through the eighteenth century.

An edition of Art’s Treasury printed in Glasgow, 1773.

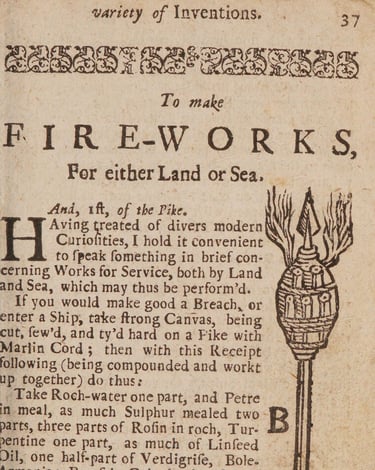

Art's Treasury contained quick instructions on making a variety of fireworks, including those to be fired into the air, and types that burned on land or water. Each started from a common ‘mould’ which housed the explosive mixture. This comprised a substantial piece of wood to which a ‘cartoush’ of strong paper or paste-board was attached, and a hole cut carefully in the middle.

To make a basic ‘sky-rocket’, readers were instructed to mix a pound of gunpowder with two ounces of charcoal, although this ratio could be adjusted by adding more charcoal if the explosion was too vigorous. Safety was paramount: a wooden mallet had to be used to pack down the powder, not an iron or stone alternative that risked sparking.

With the basics down, readers were free to get creative. Art's Treasury taught a host of different types of firework, including ‘Golden rain’, which was intended to ‘descend in the air like rain’. This involved goose feathers stuffed with the powder mixture in the quill, and added to the head of the standard rocket. Observing at a distance, this would look like ‘the blazing tail of a comet, or golden hair’.

Fireworks instructions in an earlier version of Art’s Treasury entitled Hocus Pocus (c.1716).

‘Saucissons’ were projectiles not unlike modern day rockets and could be added in bulk to a ‘fire box’ to produce a sequenced display. Arranging rockets in a circle created a ‘fire wheel’, which must have been rather like a modern Catherine wheel. ‘Silver stars’ imitated the heavens. Ball-shaped fireworks called ‘fiery globes’ were to ‘blaze like as if a comet or blazing star were ascending’.

Imagery so potent should remind us to be cautious in assuming people actually followed the instructions in books such as Art's Treasury. Getting a glimpse of how these pyrotechnic projectiles were produced, allowing the reader to imagine such a display in their mind’s eye, was still a decent return on the shilling (a few pounds in today’s money) that one of these manuals cost.

But the inclusion of fireworks in such a book was no trifling curiosity, and in fact typified a rich tradition of pyrotechnic exploration in scientific books.

Science and spectacle

Art's Treasury of Rarities was by no means the first printed book to discuss fireworks. In 1635, the soldier John Babington’s Pyrotechnia, was the first English-language book on recreational firework making. In continental Europe, the tradition went back further still.

As Simon Werrett has shown, fireworks were of genuine importance to early modern science. Since the Chinese invention of gunpowder was imported to Europe sometime in the late Middle Ages, craftsmen, soldiers, and scientists all sought to harness its explosive potential. Firework recipes became a staple of ‘books of secrets’, the early modern equivalent of popular science books.

Perhaps the quintessential example of the genre was Giambattista Della Porta’s Magia Naturalis (Natural Magic), which was first published in Naples in 1558 and translated into many European languages over the next two centuries. Magia Naturalis contained a whole chapter on ignes artificiales (artificial fires), setting a precedent for later works like Art's Treasury.

In these books there was little divide between mundane household tips, amusing anecdotes, fanciful magic, and genuinely cutting edge study of the natural world. Scientific enquiry was fused with wonder, entertainment, and mystery about natural phenomena. No wonder, then, that fireworks proved to be an ideal topic for these books.

Alongside their popularity in print, through the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries firework displays became a popular form of entertainment among nobility and laity alike. English queen Elizabeth I was a noted fan of pyrotechnic displays, and by the early seventeenth century the English royal court was spending the modern equivalent of hundreds of thousands of pounds on fireworks annually.

A fireworks display over the River Thames, London, 1749.

The French king Louis XIV used fireworks displays to astound visitors and show his power, and subsequently in France, as elsewhere, such displays became a commercial enterprise accessible not only to royalty but common people, especially in times of festivals and celebrations. Sound familiar?

Fireworks night

In Britain, perhaps the best known use of fireworks is Guy Fawkes night, an event commemorating the anniversary of the Gunpowder Plot on 5th November 1605. In a time of growing oppression of the Catholic faith, Fawkes and his co-conspirators attempted to assassinate King James VI & I by blowing up the House of Lords using large quantities of gunpowder.

Since its very beginning, then, ‘Gunpowder Treason Day’, was synonymous with this explosive mix of sulphur, charcoal, and saltpetre. Almost immediately after the plot, Protestant authorities keenly advocated the annual celebration of the event with sermons of thanksgiving, bonfires, effigy burning, and – you guessed it – fireworks. And so the effects of gunpowder entered popular consciousness as never before.

Given the ubiquity of celebrations on the plot’s anniversary, the making of fireworks must also have been a common task throughout Britain’s Protestant communities, even if gunpowder remained expensive and difficult to obtain. Whereas large-scale fireworks displays like those put on for royalty might demand the services of military engineers, the making of simple squibs for a local celebration would not have required such expertise.

Perhaps, then, when parishes up and down the country needed to bring in 5th November with a bang, a cheap manual like Art's Treasury of Rarities would have been just the trick.

Sources

Michael R. Lynn, ‘Sparks for Sale: The Culture and Commerce of Fireworks in Early Modern France’, Eighteenth-Century Life, 30 (2006), pp. 74–97.

Simon Werret, Fireworks: Pyrotechnic Arts and Sciences in European History (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2010).