In our modern world, books are more or less everywhere. They are relatively inexpensive mass-produced objects made from paper of varying quality, but before printing became the norm (in western Europe, at least) all books were also unique and precious works of art.

The reason why medieval books were so expensive and relatively rare is mainly to do with the quality of materials, the amount of labour, and the level of expertise that went into making them. This is also why many of them are in pretty good nick even after a thousand years. In this post, we would like to take you through some of the areas of knowledge, and the large number of different experts and artisans, that were crucial for medieval book production.

Jump ahead…

What are medieval books?

We often refer to medieval books as manuscripts (i.e., handwritten, from the Latin manus – hand, and scriptus – written), since every book was written by hand. This process was laborious, time consuming, and could lead to mistakes in the text. It also made each book a completely unique work of art.

In terms of their format, most medieval manuscripts are codices. A codex is a bound book with pages that you can turn, unlike a scroll which you need to unravel and is much harder to browse. Codices became popular around the fourth century CE and eventually replaced the scroll within a few centuries.

Most books were written on parchment, that is, the treated skin of an animal. While not suitable for vegans, parchment is a fantastically useful and resilient material (if kept under the right conditions) unlike the more fragile papyrus which it replaced. Later in the Middle Ages, paper – a wonderful invention from China – was introduced to Europe and gained popularity throughout the late Middle Ages.

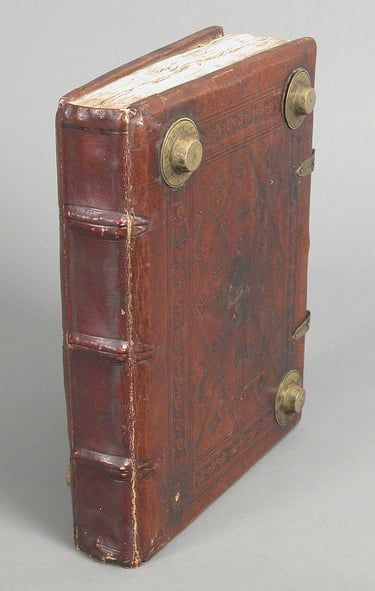

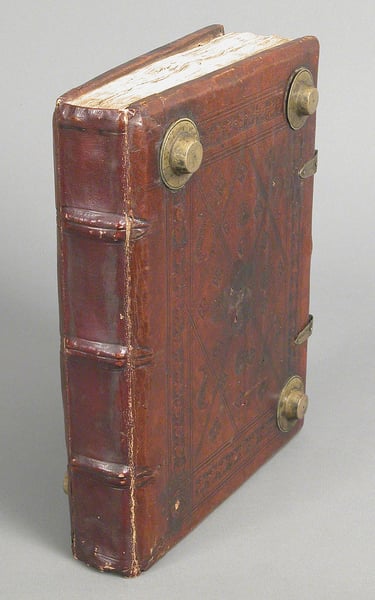

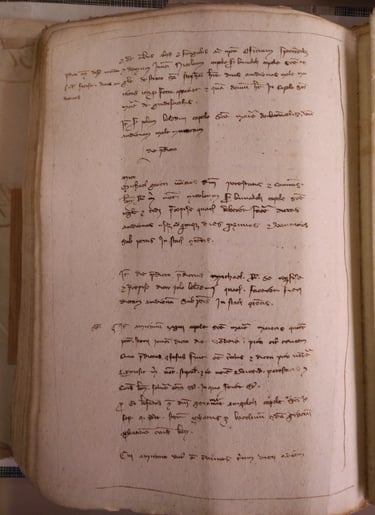

A fourteenth-century codex made from paper at the archive in Parma.

The Parchment

First, you must have an animal slaughtered and skinned. It depends on where you were in Europe and how much money you could spend, but the common ones were cows, calves (from which vellum – a more delicate and prestigious type of parchment – was made), sheep, and goats. The meat could be sold at the butcher’s, and the skin would have to go through several stages of preparation before you could put pen to parchment.

The skin would be soaked in a lime solution (and if you’ve just eaten maybe skip ahead), whose alkaline quality helped loosen the hair and leftover bits of flesh still stuck to the skin.

After a few days the skin would be stretched over special wooden frames and over a period, scraped, and stretched and scraped again, until it was clean and in the desired thickness. The process is described as rather unpleasant, and we talked about it here.

At this point the parchment can be cut into sheets. The scraps didn’t go to waste either and were used in binding, as scrap sheets for making notes, and so on.

Producing parchment required several artisans to have specialist knowledge in quite a few areas: rearing (and later, butchering) animals, chemically treating the animal skins, as well as artisanal experience in stretching and scraping the parchment without damaging it too much (and mending it when needed).

Paper

Paper was a different event altogether. It was a great technological innovation which made stationary cheaper and more available for everyday uses, and you didn’t even need to kill anything to make it. Paper in the Middle Ages was made from cellulose that usually came from old fabric (mainly rags) which after a bit of processing and a good long soak in water was beaten into a pulp and arranged on moulds made of a wire sieve.

Markings from the wire sieve mould visible on a paper record from fourteenth-century Parma when held against the light.

It was then left to dry and any remaining water was pressed out and eventually sheets were dipped in gelatine to size them. This process reduced the paper’s absorbance and made it very durable (I had the pleasure of handling some really pristine paper records that were well over 700 years old).

Despite paper becoming more ubiquitous and popular as a writing medium, parchment (and particularly vellum) remained the most prestigious material especially for texts of particular importance. A notable example would be Torah scrolls, and even the House of Commons used vellum for printing public Acts of Parliament until as late as 2015.

This process described here only in the broadest of strokes entailed a rather refined understanding of mindbogglingly complex biochemical processes. Even if some of it was more intuitive than what we might call scientific, there was a huge amount of knowledge and experience that went into operating a paper mill.

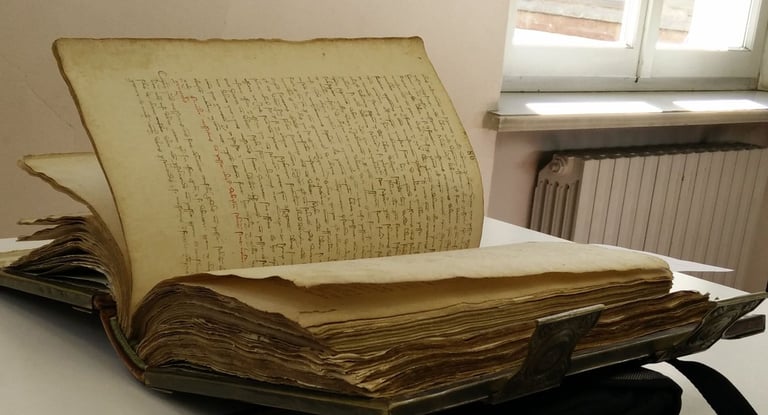

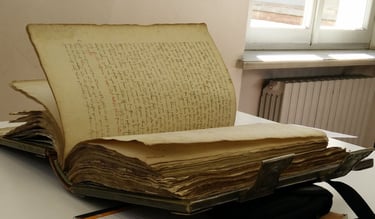

Paper records from 1302 Bologna. Notice how by folding the page twice the scribe was able to find the middle of the page and its margins.

The ink

Black ink was commonly made from oak-galls. These are ball-like growths which are caused by wasps laying eggs in the buds of an oak tree. These were soaked or boiled to extract certain acids (the acidity of the ink enabled it to adhere to parchment better), and were mixed with other ingredients such as metallic salts or iron sulphate which made it black.

While the standard ink was black, initials and rubrics which helped break the text and make it more legible and aesthetically pleasing used colours (the word rubric comes from Latin rubor, meaning red). There were all sorts of recipes for ink to achieve different pigments most commonly red, green, and blue as well as the more exotic yellow, purple, pink and orange and even gold and silver.

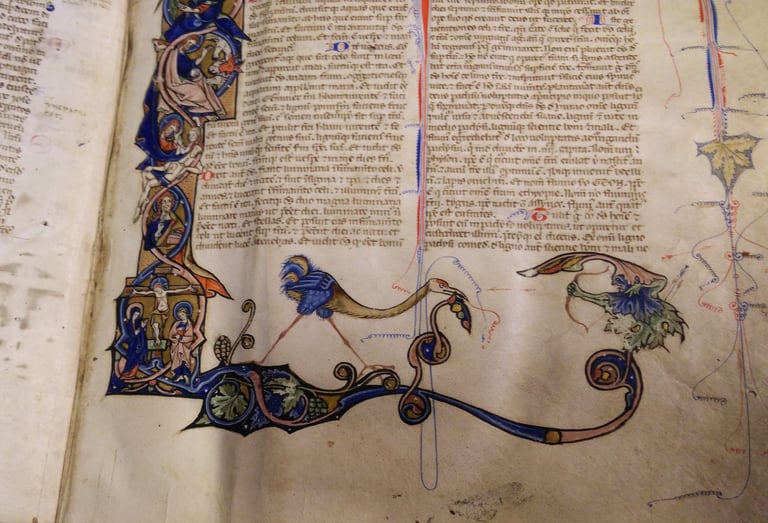

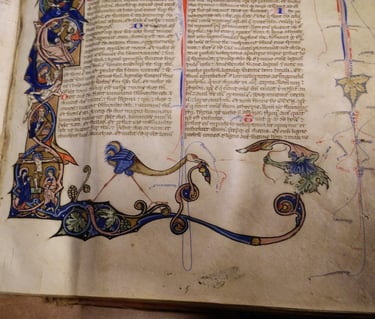

A lavishly decorated page of a bible, 13th Century, Italy.

The various recipes to produce these pigments are not dissimilar to alchemy and demanded precision and accuracy in everything from sourcing the right ingredients to meticulously following the chemical process to get good ink.

Quills

The most common writing instrument in medieval Europe was the quill pen, made from the feather of a bird. Feathers are quite sturdy, flexible, and light. They are also conveniently hollow, so whenever dipped, they store some ink inside. The best thing was to get a live goose and pluck a long feather from its left wing (it’ll grow back eventually). Why the left? Because when held by a right-handed person, the quill will naturally curve in the right direction and won’t get in the way. Feathers sourced in springtime were generally considered best.

After you got your feather, a sharp penknife would then be used to shape it into a pen and trim the fluffy bit that doesn’t really serve any purpose. The scribe would also wield their penknife to sharpen his quill whenever the tip became a bit dull, and also to scratch ink off the parchment whenever they made a mistake.

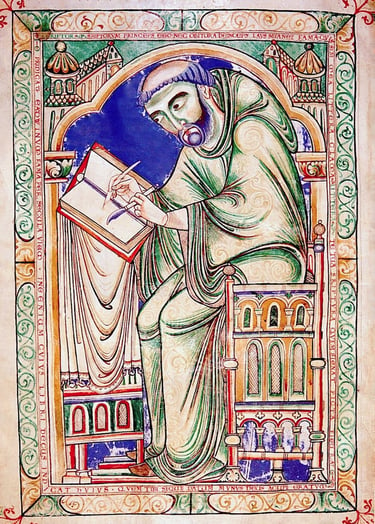

A scribe using a quill and penknife in a 12th century English psalter.

Unlike with the production of other stationary, it is hard to find a modern discipline (like chemistry or biology) that fits the kind of knowledge used for making quill pens. Yet, knowing what materials to source and how to prepare them was clearly much more artful than walking into a stationary shop.

Copying the text

All writing materials prepared, it now comes to the scribe to copy the text. The act of writing itself took quite a bit of training. It is not only managing a pen and the flow of ink but also spelling and grammar which help to reduce mistakes when copying text.

Scribes also had to arrange their parchment or paper into quires, or gatherings, which were usually four sheets which were folded to make eight leaves. Each leaf or folio had two sides, a recto and verso (abbreviated as r. and v., which is why you might find references to manuscripts looking like this: f. 23v, that is, folio number 23 on its back side).

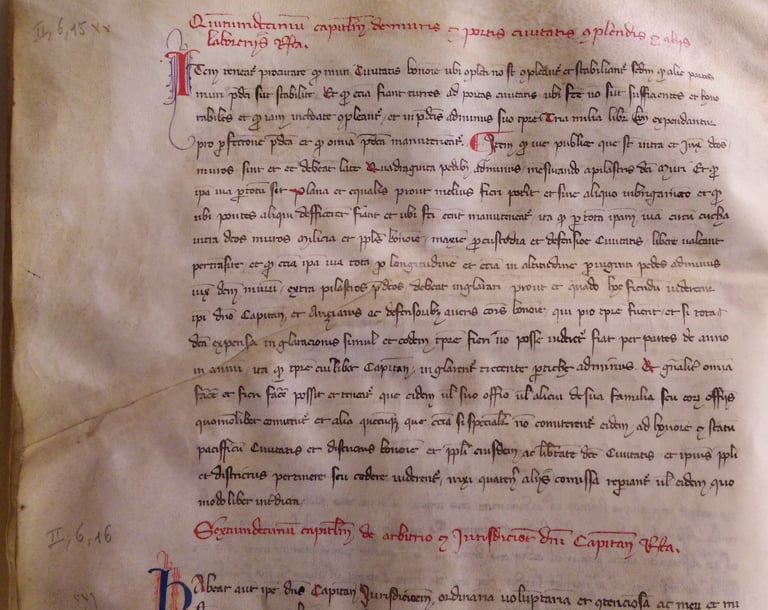

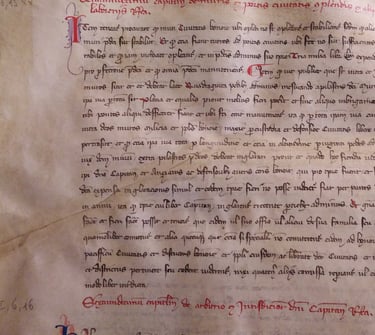

Since the task of writing is arduous and time consuming, and writing materials were expensive, scribes employed a rather elaborate system of abbreviations to expedite things. For example, you could save yourself the bother of writing the letters n or m by placing a horizontal line above the vowel that comes before. Instead of writing the word et (meaning and) you could just write 7. Adding a 9 at the start of a word would add the prefix con- and above the line at the end of the word it would make the suffix -us. The word dominus (lord)? Just write dn͡s.

Here are some other common abbreviations: ꝓ (pro), ꝑ (per), ꝗ (qui), ꝙ (quod), ꝝ (-rum).

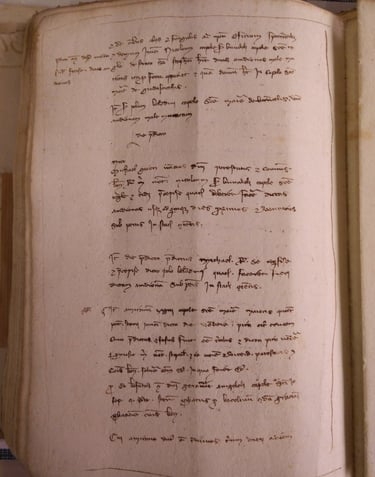

A page with abbreviated legal text from 1335 Bologna.

These abbreviations (while annoying to the modern reader) were considered so useful that we find them in early modern print as well. Some texts would be more or less abbreviated. As a rule, fancier books (like a big illuminated bible) would have fewer abbreviations than, let’s say, plain administrative records.

Before copying the text, the scribe would also arrange sheets of parchment or paper into quires, normally containing eight leaves. These needed to be kept in the correct order so that later when binding them together the book would make sense.

Illuminations and illustrations

Because manuscripts were almost always commissioned, there was quite a lot of room for customising them. Some came with almost no decorations, written exclusively in plain black ink, but the posh ones would have magnificent multicolour illustrations and illuminations. These can take the form of an initial, a part of, or even an entire page.

While illustrations are drawings in one or more colours of ink which could be little more than doodles or wonderfully elaborate works of art, illuminations are specifically images that use precious metals such as gold and silver leaf which reflect the light (or lumen in Latin, found in illumination).

An illuminated page from the Lindisfarne gospels (7th century).

Gold was more common than silver, which oxidised more and lost its shine, and could be used either in pulverised form mixed with gum or as a gold leaf – an extremely thin sheet of the precious metal.

There were different techniques for applying gold; in pulverised form it was applied last after all the other colours were on the page with a pen or brush, while in leaf form it was applied first using some egg white (which was later replaced by gesso made from white lead, some sugar, and a reddish clay that made it pink). It was then thoroughly burnished before other colours could be applied.

This luxurious art required knowledge of painting, delicate metalwork, and an understanding of chemistry for making good adhesives.

Sources

One of the best beginner’s guides to medieval manuscripts is:

Raymond Clemens and Timothy Graham, Introduction to Manuscript Studies (Ithaca, 2007).

The definitive authority on palaeography and abbreviations is Adriano Cappelli’s Lexicon Abbreviaturarum (first published in 1899), which was made available and searchable online by the University of Zurich:

https://www.adfontes.uzh.ch/en/ressourcen/abkuerzungen/cappelli-online

Binding

Finally, the book is written, decorated and assembled in the right order so it is time to bind it together. This could be done with just some parchment covers or a hard wood binding, often covered with leather.

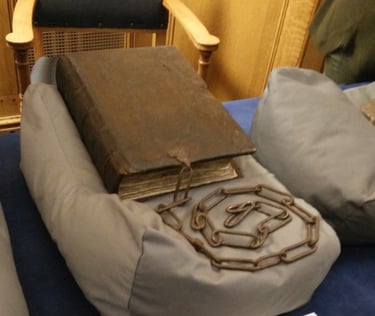

A bound manuscript with a chain (which attached it to the shelf so it won’t go missing) at the University of St Andrews.

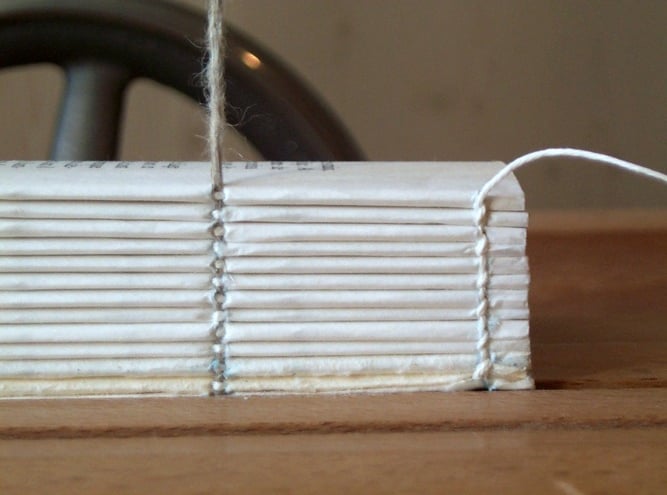

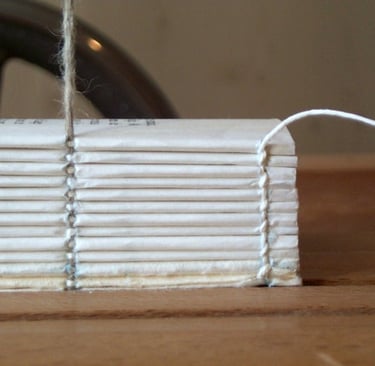

This was another highly specialised job that involved sewing the quires one by one onto a leather sewing support using a special frame. The loose ends of the sewing supports would be attached to the boards, which would be covered in another sheet of parchment using paste. Some very fancy covers would also have ornaments in metalwork and even precious stones attached to them.

Using the magic of thread work, carpentry, adhesives, and goldsmithing, binders made exquisite or sometimes just useful covers to protect those valuable manuscripts.

Considering how many types of knowledge, scientific and artisanal, as well as experience accumulated over centuries it is hard not to develop an appreciation of medieval manuscripts. Even though the printing press and cheaper materials revolutionised book production, our modern printed books are very much like their medieval ancestors; they are codices made of quires which are sewed or glued and bound together in much the same way. The form arrived at by medieval people is so perfect that not even e-readers have managed to replace it.

Quires being sawn together.