In the early nineteenth century, Sweden was experiencing an identity crisis. While much of the previous emphasis was on Sweden as the homeland of the warrior Goths, a germanic people who played an important role in the late Roman Empire and the early Middle ages, á la Olof Rudbeck the Elder, they now had to share the spotlight with the Vikings, who lived between the eighth and eleventh centuries. The National Romantic movement ushered in a ‘rebrand’ of the warrior Swede, with an emphasis on longships, drinking horns, and rune stones. But where did this idea come from? And how did it affect people’s understanding of the Swedish landscape?

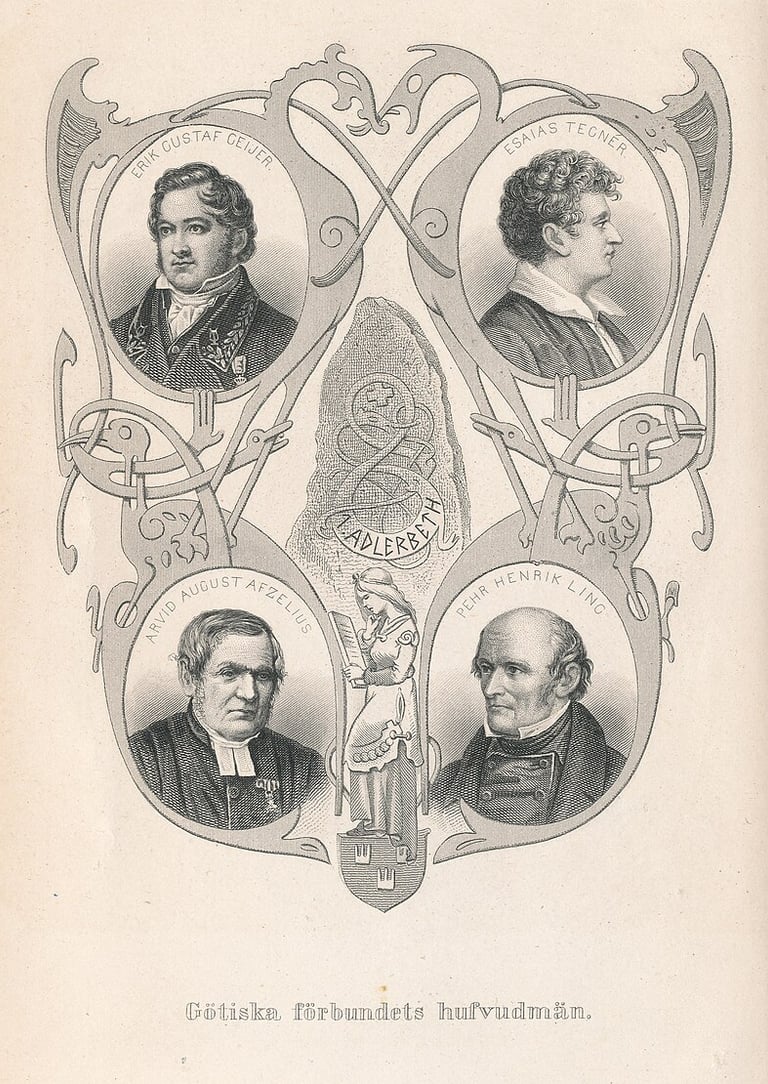

Rodulf Hjärnes 'Götiska Förbundet och dess hufvudmän', 1878.

A National Identity Crisis

The beginning of the nineteenth century had been challenging for Sweden. Various wars had chipped away at its Baltic Empire, culminating in the loss of Finland to Russia in 1809. With the exception of Swedish Pomerania, which was lost in 1815, losing Finland essentially solidified the borders of Sweden that we recognise today. It is important to remember here that in just a century, Sweden had gone from a substantial empire with control of the Baltic Sea, to a nation now worried about its ability to continue to exist.

It was against this backdrop that Götiska Förbundet, or the Gothic league, was born. It was founded in 1811, starting out as a joke between Jakob Adlerbeth and his friends. However, driven by the ambition of Adlerbeth, it soon became more serious. According to the society’s statutes, it sought to ‘recreate the spirit of freedom, masculine bravery and common sense from the old Goths’. This, they believed, could be done by cultivating knowledge of the past.

They hoped that it would help Swedes find the strength to fend off the existential threat posed by Russia. Recent Swedish history, they decided, was too loaded with loss and defeat. So, to find inspiration, they looked further back, to ancestors from ancient days. The invention of a national myth through the study of the past was therefore a direct aim of the society.

Mead, Myths and Masculinity

So began their project to gather knowledge of the Nordic past. Academics, military officers and statesmen came together to bring this work to life. The Gothic League’s works were wide-ranging, and encompassed ideas from gathering regional folk songs, translating the Sagas from old Norse and collecting rare historical documents, to nationalist gymnastics programs, historical essays and, crucially, cataloguing the ancient remains. To spread their work, they created a journal, Iduna, named after the Norse Goddess of youth.

The society was not just concerned with academic matters – it was also a social club. They would hold regular meetings and dinners, and would drink mead from bragebägaren, a drinking horn. This was an especially important part of their practice, as they did it to mimic the way Viking warriors would come together to drink and share stories after battle. It was also a masculine practice; the society was a brotherhood, and, as Adlerbeth stated in a speech to the group in 1812, it wanted to bring about the ‘the reawakening of our forefather’s masculine bravery and fair minds’. The Viking mimicry may appear to contradict the “Gothic” aspect of the Gothic League, but it is important to remember that their focus was on capturing the greatness of Sweden’s glory days, rather than historical accuracy, leading to seemingly contradictory focus points. While the Vikings were viewed positively within the society from the get-go, it is also worth noting here that they had a negative reputation throughout the rest of Europe, due to writers like Alcuin and Bede, who wrote popular and widely read texts on the Lindisfarne raids.

They also took on pseudonyms from the ancient and sometimes mythical past of the Eddic tradition and heroic sagas, with names including Baldur (a Norse God), Bosi (from the Icelandic saga Bósa saga ok Herrauðs) and Starkotter (a heroic figure who appears in Beowolf and Herverar Saga, as well as skaldic poetry). To become a full member, they had to write a poem about their namesake and read it to the rest of the society at a meeting. Many of these practices had questionable historical basis but were an important part of the reinvention of the Nordic cultural project of the Gothic League

Runestones and the Swedish Landscape

So where do the Vikings come in? While the word ‘Viking’ had been in use in Anglo-Saxon sources from the eleventh and twelfth centuries, it was a member of the Gothic League, Erik Gustag Geijer, who popularised the modern image and term his poem Wikingen (The Viking, written in 1811). It tells the story of a fifteen-year-old boy going on a Viking raid.. This poem was a notable success for the society – it was translated into English and published in Britain. According to the meeting minutes of the society in 1814, the poem was ‘with great applause being sung by the inhabitants of Great Britain’. Not only were they inventing the idea of the Viking, but they were spreading it overseas!

An important part of the popularisation of the Viking included the study of Norse history. The Vikings didn’t leave many written sources, but what they did leave were runes. Runestones were, and still are dotted across the Swedish landscape, and many can be found in the countryside. However, many people, including the antiquarian Nils Henrik Sjöberg, were worried that these remains were under threat from industrialisation. While not a member of the society, Sjöberg corresponded with Adlerbeth, and shared his aims of preserving the archaeological runic sites. Together, they drew up a plan for how to preserve knowledge of these historic sites.

Travel Writing as Knowledge Preservation

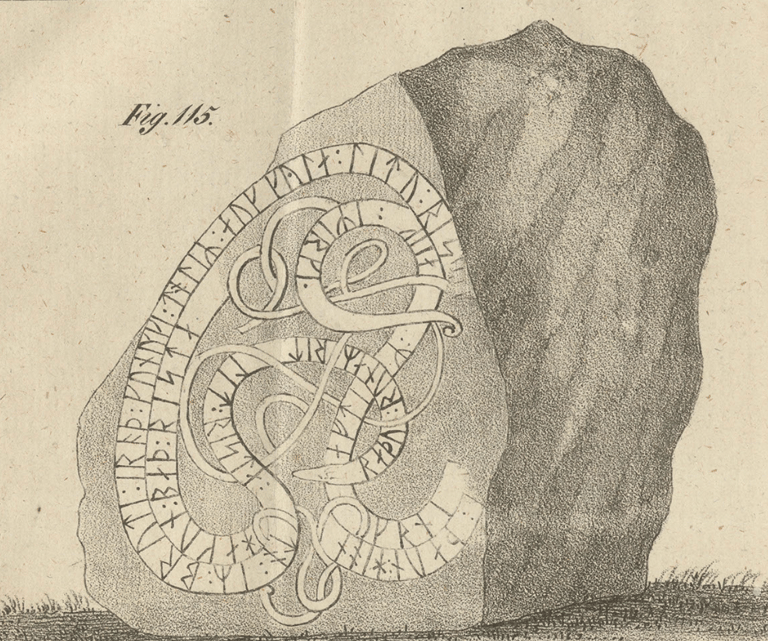

Thus, projects to catalogue the runes began. To do this, they would need people to travel across Sweden and write down descriptions of the sites. Domestic travel, with accounts much like those written during colonial Grand Tours were being produced, all in the effort to build a stronger knowledge base of the Swedish landscape. One example of this Adlerbeth’s writing, which was centred around the island of Visingö, in lake Vättern, near Jönköping in the south of Sweden:

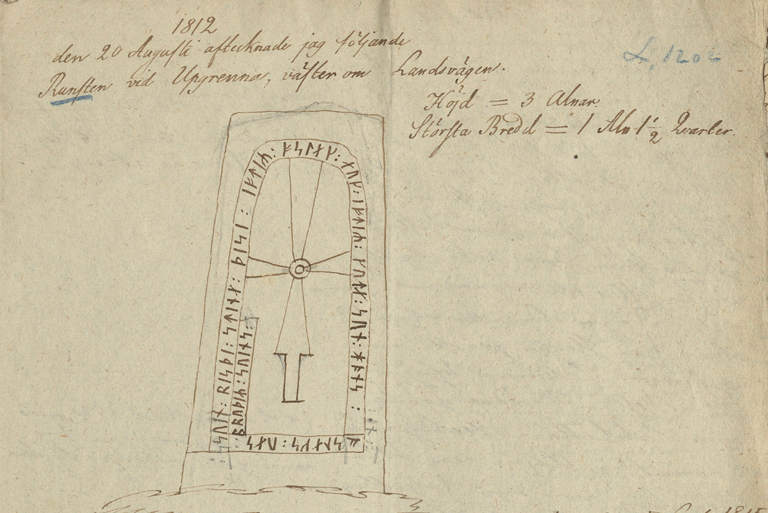

SE/ATA/ENSK50-1_F 4B_15 Jacob Adlerbeth drawing

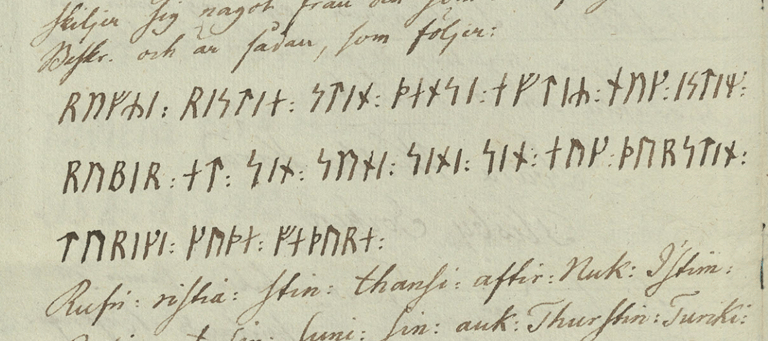

Götiska Förbundet received many descriptions of this nature from its wider membership, such as the written account by J. J. Lagergren:

Many of these travel accounts would then be rendered in more detail and published in Iduna:

SE_ATA_ENSK50-1_F 4B_14A

Björkö, Östra Härad, Småland, submission to GF, J J Lagergren SE_ATA_ENSK50-1_F 2A_10

Epilogue

The end result of these projects can be categorised as ‘complicated’. The drive to preserve the runes has certainly been a success. If you spend any time in Sweden, you’re sure to stumble across them.

Rune in the town centre of Vallentuna, Sweden

The runes themselves are now searchable in an online database. However, it is also important to keep in mind that contemporary Swedish nationalist movements are deeply dependent on the reinventions, knowledge and imagery which came out of the national romantic movement of the early nineteenth century. The practices of Götiska Förbndet and other participants of the movement did not just preserve the past, but actively reshaped societal perceptions of it: the image of the Viking was, after all, grounded in the desire to create a nationalist brotherhood in the image of masculinity and violence. This should prompt us to take care of how knowledge is made (and twisted) to suit political aims, as well as the motives behind knowledge production, and be critical of what images come out of it.

Sources

Stockholm, Riksantikvarieämbetet

SE/ATA/ENSK/50-1/FA-A. Meeting minutes dated 28th March 1814. “Anteckningar vid Göthiska Förbundets Stämmor år 1814”

SE/ATA/ENSK/50-1/FA-A. STADGER FÖR DET GÖTISKA FÖRBUNDET