A previous post on this blog explored a twelfth-century bestiary which drew on the common trope of beehives as analogous to a model society. Observers since ancient times praised bees for their strong monarchical rule and for being diligent, obedient subjects who lived, worked and died for their hive.

In England, the popularity of beekeeping books was only growing in the seventeenth century. Yet this was a time of changing opinion about what beehives represented. Notions of an idealised hive seemed ever less compatible with a society that was being stretched and strained by violence, socio-economic polarisation and vast shifts in understandings of the natural world.

It must have been hard to buy into books about a harmonious monarchy after the king, Charles I, was executed in 1649, following hellish civil wars that saw more lives lost per capita than the First World War. Political radicalism thrived. Great plague and fire were signs of providential rage. The century to 1650 saw a gargantuan divergence in the wealth of rich and poor. This was, as a contemporary ballad put it so memorably, ‘the World turn’d upside down’, and all was not well in the hive.

An early pamphlet printing of The World Turn’d Upside Down (1647).

Buzz words

Concepts of ‘order’ and ‘commonwealth’ were integral to moralistic discourses about English society in the sixteenth century. The commonwealth, contemporary writers hasted to stress, was a harmonious, just and prosperous society content under the king’s authority. As Keith Wrightson points out in an introductory lecture to sixteenth-century society, the concept of ‘order’ was one of which ordinary people were constantly reminded.

In the beehive, different types of bee performed various functions according to their ‘rank’. In this the reflection of early modern England’s rigidly hierarchical social structure was there for all to see. Even a cursory look at the titles of some early English works on beekeeping shows how readily the language of ‘order’ could be applied to apicultural practices. The first Anglophone work on the subject, which appeared in 1568, was titled A Profitable Instruction of the Perfect Ordering of Bees, appended to the third edition of Thomas Hill’s The Profitable art of Gardening. There were other titles like The Ordering of Bees and A Sure Way to Order Bees and Fruit Trees. John Thorley’s Melissēlogia (1744) was billed as ‘an enquiry into the nature, order, and government of bees’.

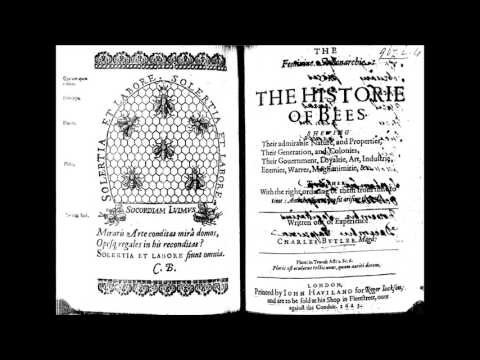

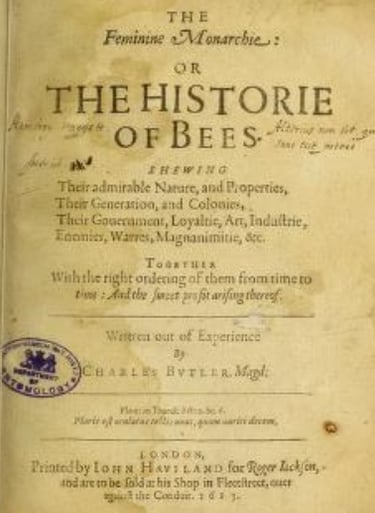

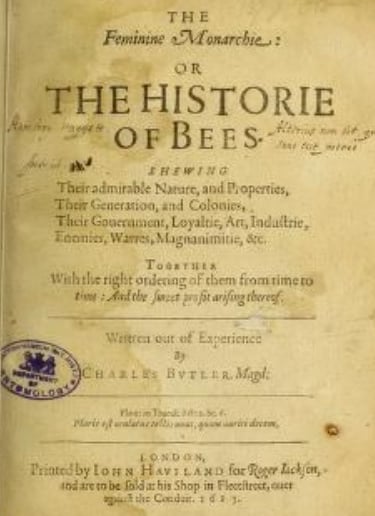

Typical was one of the most important beekeeping English books to appear at this time, Charles Butler’s Feminine Monarchie, which was first published in 1609 and substantially expanded in 1623. The work began with a poem that praised ‘this Common-wealth of Bees’ and ‘How they Agree… How seriously their Bus’nesse they intend; How stoutly they their Common-good defend’. Butler upheld the long-standing belief that in the bee was visible ‘An Abstract of that Wisdome, Power, and Love, Which is imprinted on the Heav’ns above’: a divine order crystallised in honey.

Butler’s Feminine Monarchy also contained a piece of choral music composed to imitate the sound of bees.

Order undone

Whether or not the social harmony depicted in bee books was ever a reality, developments over the seventeenth century altered the complexion of these works fundamentally.

The development of a capitalist economy and consequent social polarisation damaged the communitarian spirit evident in earlier books, and instead individual prosperity was the order of the day. These books quite consistently promised ‘profit’ on behalf of those who followed their instructions, but the meaning of profitability shifted.

In early seventeenth-century texts such as John Levett’s Ordering of Bees (1634), the aim of beekeeping was framed in religious terms: ‘the profit of this booke’, he argued, was ‘the successe that it shall please God to give in the use of it’. A later-century text, John Worlidge’s Apiarium (1676) struck a quite different tone, replacing talk of a cohesive and harmonious commonwealth with that of individual success, laced with the language of ‘improvement’ characteristic of the day.

Worlidge was writing in light of more recent work by those ‘who are willing to endeavour an Improvement and Advancement of Bees’, to make them ‘more profitable’ and productive. He was somewhat dismissive of those ‘most learned and accomplished Poets and Philosophers… who after all their subtil disquisitions into the Natures and Properties of them [bees], have ever concluded with admiration of their Vertues and their Knowledge, Order, Government, Art and Industry’.

Long treatises on bees which fused utilitarian instruction with social commentary didn’t disappear, but a new raft of beekeeping books emerged which took a wholly practical approach. In reality, this was probably closer to what people actually wanted, as I discuss in another blog post. Perhaps ideas about hierarchy and obedience – not to mention the copious Latin passages and classical allusions visible in works like Butler’s – were not so attractive to most ordinary readers.

Worlidge’s A Sure Way to Order Bees and Fruit-Trees, c.1720, sold by the how-to book specialist George Conyers.

The years around the turn of the eighteenth century saw a growing democratisation of knowledge thanks to rising literacy and growing production of cheap how-to books. Examples like the twelve-page booklet, A New and Compleat Bee-master (c.1710) left no room for moralising. There was only practical information and advice, and the text ended with an emblematic reckoning that if one spent five half-crowns on ‘stocks’ of bees, they might nurture twelve stocks in one year, thirty in two, and a hundred in three years, generating revenue of £25 at 5 shillings per stock. Tasty.

The new science of bees

If new notions of individual profit were these books’ selling point, their intellectual foundations lay in new scientific advances. Since the beginning of the seventeenth century, the empirical science advocated most famously by Francis Bacon, based on experimentation and observation rather than the received wisdom of the ancients, showed its influence on these works. While the first English beekeeping book, Hill’s Profitable Instruction, was simply a translation of an older German text which itself drew on classical ideas, newer authors at least tried to be more innovative in creating knowledge.

New discoveries about the workings of beehives challenged existing assumptions about how their inhabitants lived. Sixteenth-century writers inherited an Aristotelian tradition which failed to accurately distinguish, among other things, the gender makeup of the hive. Mating among bees was impossible to observe because it took place in flight, and so it remained widely held that the hive was run by a male king.

1623 edition of Butler’s Feminine Monarchie.

Butler’s Feminine Monarchie was a key work that suggested the supreme bee was in fact a queen, but in England it remained a matter of debate until the findings of dissections by the Dutch entomologist Jan Swammerdam were disseminated a century and a half later.

If Butler’s text could at once perpetuate ancient ideas about idealised monarchical societies while also helping to generate new knowledge gained by observation, it demonstrates how important beekeeping was as a subject of enquiry about the natural world in the early modern period. The all-too-useful analogy of the beehive as a model society remained prevalent through the eighteenth century, but a range of practical books based on experience had come to coexist with them.

Whether beehives were seen as genuine evidence of God’s design, a mere metaphor for divine order, or simply a means of harnessing the natural world, few authors disputed what we still hold true today, that bees are an essential part of the natural world and they must be protected.

Further reading

Adam Ebert, ‘Nectar for the Taking: The Popularization of Scientific Bee Culture in England, 1609–1809’, Agricultural History, 85 (2011), pp. 322–43.

Frederick R. Prete, ‘Can Females Rule the Hive? The Controversy over Honey Bee Gender Roles in British Beekeeping Texts of the Sixteenth-Eighteenth Centuries’, Journal of the History of Biology, 24 (1991), pp. 113–14.