The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has featured several times on this blog, normally in relation to knowledge within or about Sweden itself. In this post, however, we’re exploring a link between this prestigious scientific institution and the Anglophone world which arose from an unlikely source.

Thomas Simpson (1710–1761) was the son of a weaver from a small market town in the English midlands. He received almost no formal education. Yet by the end of his life he was one of Britain’s best known mathematicians and among the first British fellows of the Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Thomas Simpson (1710–1761)

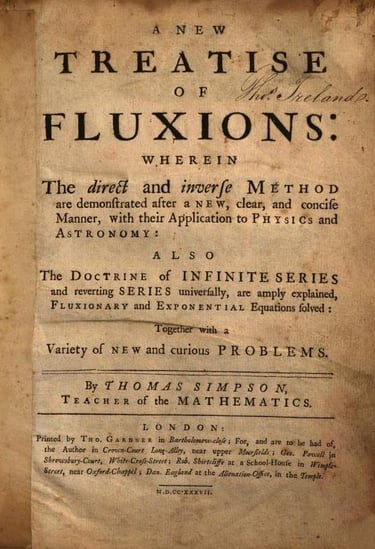

A New Treatise of Fluxions (1737), Simpson’s first book.

The follow-up, Essays on Several Curious and Useful Subjects (1740) contained methods for finding the position of stars, accounting for the movement of the earth and shifting position of celestial objects as light travels, in some ways echoing the interest he’d shown in the itinerant astrologer years earlier.

Through the 1740s, Simpson became established as a headline act on London’s circuit of coffee-house mathematical lectures. He was soon appointed to a prestigious post as assistant master at the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich, and wrote a number of bestselling textbooks which saw multiple editions. He also gained some renown for publishing answers to the mathematical questions in a popular annual periodical called the Ladies’ Diary, and eventually rose to become its editor.

In recognition of his achievements, Simpson was elected Fellow of the Royal Society, Britain’s preeminent scientific institution, in 1745. Later, in 1758, he received the same honour from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, making him one of the earliest British inductees.

The only Brits to predate him in the Swedish institution were the astronomers James Bradley and George Parker, 2nd Earl of Macclesfield; the botanists Peter Collinson and John Clayton; the clockmaker John Ellicott; and two other mathematicians, Colin Maclaurin and Martin Folkes, the latter of whom was instrumental in having Simpson elected to the English Royal Society.

Intellectually elite, socially precarious

From his inauspicious beginnings, therefore, Simpson rose to the world of metropolitan coffee-houses, scholarly publishing, and learned societies. But intellectual ability took him only so far.

Through his prowess he gained the esteem of several powerful members of the Royal Society in London. They were willing to propose his election, but equally had to ensure he would be excused of the burdensome admission fee. Socially, he was not the typical Royal Society Fellow, and seems to have felt more comfortable among the tradesmen who made up the Spitalfields Mathematical Society.

According to Hutton’s biography, the living that Simpson made through his teaching was tested by his wife and children’s extravagant spending, though the large quantities of cheap alcohol he consumed can’t have helped matters, and he remained unable to afford the lavish lifestyle of a gentleman. These strained circumstances and the emotional stress of tireless work ultimately caused his decline and early death.

Though Simpson’s unique talent saw him become one of the foremost mathematicians in the country, his story of relatively lowly provincial beginnings, teaching himself mathematics, and making a living by passing on his knowledge, was in fact anything but uncommon.

Consider, for comparison, the case of Henry Beighton (1687–1743), examined in a recent book by Steve Hindle. Like Simpson, Beighton came from a middle-ranking family from the Warwickshire parish of Chilvers Coton, right by Nuneaton, where Simpson lived for some years. Beighton too learned mathematics largely of his own volition and became a renowned engineer and surveyor. He too was sometime editor of the Ladies’ Diary and was elected Fellow of the Royal Society in 1720, but never attained the wealth or status of the gentlemen who comprised the bulk of fellows. And like Simpson, he died suddenly with his finances in poor shape.

The stories of both Beighton and Simpson offer a fascinating demonstration of how intellectual achievement could leave people in an uncertain and precarious position in the social order of eighteenth-century Britain. One reading of Simpson’s life story is that of someone who rose from the position of a weaver’s son, fortune teller and schoolmaster in a provincial locality, to that of a renowned author, editor of a periodical, and member of elite learned societies domestically and abroad. Another is that of a man never closer than the fringes of the metropolitan intellectual and social elite, whose tireless work was ultimately the source of his decline.

We might also reflect on the story of Simpson’s life, handed down through sources like Hutton’s biography. Though it may indeed be entirely true, the picture painted of Simpson’s humble beginnings, innate talent, and slightly fish-out-of-water persona has an undeniably hagiographical quality to it. The anecdote about his use of Cocker’s Arithmetick, for example, may be a simple statement of fact, or perhaps instead a literary trope designed to play on contemporary recognition of that textbook’s absurd popularity as a symbol of mathematical autodidacticism.

Such stories of social mobility were themselves characteristically eighteenth-century phenomena. Simpson evidently lived at a time when mathematics was at once the domain of astrologers and fortune tellers, a practical subject learned from cheap textbooks acquired from travelling salesmen, while at the same time the subject of intellectual enquiry in the country’s elite scholarly institutions.

The fact that a weaver’s son from an inconspicuous provincial town with little formal education could attain such dazzling heights only serves to underscore the peculiar place of mathematics in eighteenth-century society.

Sources

Of all the sources consulted for this post, a special mention is owed to MacTutor, a website hosted by the University of St Andrews, which is an outstanding resource for the history of mathematics.

Frances Marguerite Clarke, Thomas Simpson and His Times (New York, 1929).

Niccolò Guicciardini, ‘Simpson, Thomas (1710–1761)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, online edn.

Charles Hutton, ‘Memoirs of the Life and Writings of the Author’, in Thomas Simpson, Select Exercises for Young Proficients in the Mathematicks, ed. by Charles Hutton (London, 1792).