At their core, recipes convey knowledge about food. In this post, we want to explore interesting recipes from different historical contexts to understand the sorts (dare we say, flavours) of knowledge visible in these written cooking instructions.

From medical texts in medieval Italy to early modern English self-help guides and scientific literature in eighteenth-century Sweden, these recipes exhibit the enormous range of motives which saw authors commit their culinary knowledge to writing. What they have in common is the goal of guiding people in staying healthy and nourishing their bodies. For, as the pre-modern authors understood, preparing food was a key ingredient not only in the health of individuals, but society at large. In turn, the way in which people prepared and consumed food says much about their place in the social order.

Culinary knowledge was key for courtiers displaying their prestige, natural philosophers attempting to maximise the production and nutritional value of foods, and for ordinary people trying to live well and affordably. And although in many cases it may have been easier for people to learn how to cook through observation and experience in the kitchen, the recipe has proved a remarkably popular and enduring means of communicating this sort of culinary knowledge.

Guiding people step-by-step in the creation of dishes was not the only way that our forebears learned about food, but it seems to have been a textual form that they found particularly informative, malleable and, above all, useful. As such, surviving examples of historical recipes tell us much, not only about what people ate and how they prepared food, but the knowledge and culture that surrounded its preparation throughout history.

Read on for three snippets of culinary knowledge in recipe form. Bon Appétit!

Jump ahead...

Who needs a medieval recipe?

Recipes and writing about food as a genre have existed for many centuries, even in Ancient Rome. One of the best-known early examples of a recipe collection is attributed to first-century AD Roman gourmand Caelius Apicius (or to a different ancient Roman, Marcus Gavius Apicius). The version of that book we have today, De Re Coquinaria, was probably composed by several authors and possibly over several centuries, but the book and its author became synonymous with recipe writing. So much so that centuries later Francesco Leonardi called his immensely influential 1790 cookbook, which put modern Italian cuisine on the map, L’Apicio moderno (or ‘Modern Apicius’).

In between these two Apician publications there were quite a few other works written during the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period discussing the qualities of food, how different foods affect one’s health, and how to best cook, preserve, and treat certain medical conditions with different ingredients.

Premodern writing about food can be quite general and seem a bit unhelpful to us. Take, for example, Anthimus, a sixth-century Greek physician who was a part of the court of Theodoric king of the Ostrogoths in Ravenna before (confusingly) moving to the court of Theudorich, King of the Franks. He wrote a treatise On the Observance of Foods where he had, among other things, some helpful advice on beer and mead:

Beer and mead that are the most agreeable of all should be drunk. As beer that is well made has purpose and offers benefits, just as the different kind of ptisan [a drink made from barley] that we make. Similarly, mead that is well made is also very helpful, as it benefits from using honey.

Yet sometimes in the Middle Ages we find actual recognisable recipes like in a fourteenth-century cookbook called Liber De Coquina (On Cooking). Here, for example, is a recipe for salsa verde (or green sauce) which is a lovely condiment that can add a bit of welcomed freshness to roasted or boiled meats:

For green sauce take parsley with mint with their stems, cardamom, nutmeg, pepper, cloves, ginger, grind it all well in a mortar and then rub into it a bit of breadcrumbs, and if you wish, you can put garlic and blend it with good vinegar.

If you want more historic salsa verde in your life, why not try here.

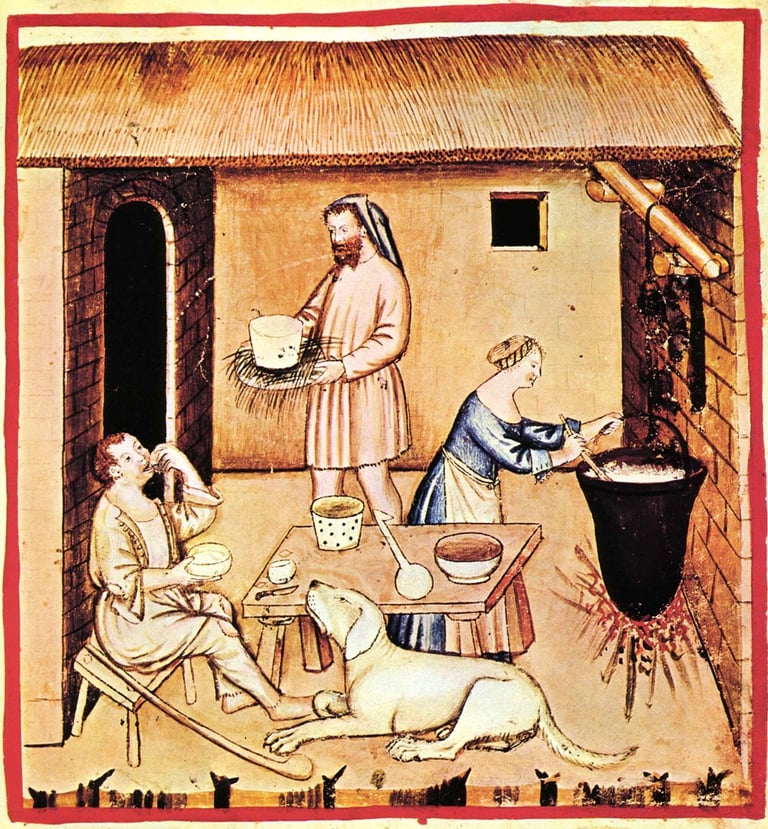

Preparing and serving cheese; Tacuinum Sanitatis, 14th century

While you may have noticed the absence of quantities or clear method like we would expect to find in later recipes, there is, however, an alarming abundance of very expensive spices added to this (usually) rather humble sauce. Cardamom, nutmeg, cloves, pepper and the like had to be imported into Europe and would have cost a fortune. This raises the question: who was this recipe for?

The person who wrote the recipes in Liber De Coquina was probably employed in an important court, and it is not only the posh or exotic ingredients, or lengthy and complicated techniques found in that book that hint to this, but also the fact that it was written in Latin on parchment (a scholarly language on an expensive material).

No medieval home cook needed such a book (even if they could afford and read it) as they would likely have already been taught how to cook, shown useful techniques and what flavours go with what by some other cook who trained them. On top of that, people always found themselves experimenting and improvising with what they could get their hands on. In a royal court, however, the head cook (which today we’d call chef) who had access, and was expected to use expensive ingredients and complicated techniques preparing food for important people, could benefit from such a book so that they wouldn’t waste money or make anyone ill.

We see, then, in the Liber De Coquina how elite culinary knowledge that was useful in a particular context was preserved for the ages, but we must remember that this was very likely not a good representation of how food was made in other parts of medieval society.

Thomas Tryon: a seventeenth-century English self-help writer on the vegetable diet

Turning to an example from seventeenth-century England, we can explore the ways in which those of lesser wealth and status encountered recipes. The fact that cooking could be learned simply through observation and experience rather than by following a recipe was no less true of Stuart England than medieval Italy. But that didn’t stop ordinary people buying recipe books, especially if they came with the promise of saving money.

One recipe author whose books offered exactly that was Thomas Tryon. In the mid-1660s the Londoner Tryon moved to Barbados, where he was ‘mightily stirred up to a more than ordinary Abstinence… and lived for some Weeks on Bread and Water’, while ‘Eggs, Milk, Butter and Cheese, and everything proceeding from the Animal Kingdom’ were off the menu. For readers of Tryon’s 1705 memoir, this recollection would have come as little surprise. By then he had established himself as a household name for the publication of self-help books recommending a meat-free diet. Subsequently he has gone down in history as one of England’s first great vegetarians.

Thomas Tryon

A spell working in London in the 1650s had brought about spiritual awakening in Tryon, and he incorporated abstinence from meat and alcohol into a lifestyle of sobriety and diligence. His efforts became concentrated on writing and he became a prolific author of practical advice and how-to books on subjects such as household management, farming and cooking. His most widely regarded work appeared in 1682 and was soon reprinted under the title by which it became famous, The Way to Health.

This work reads in some ways like a profoundly modern piece of self-help writing. For Tryon, bodily health was a quality over which readers could affect their own agency. His purpose was ‘to perswade them [his readers] to be kind to their own Healths, their own Lives, their own Souls’. The answer, of course, was modesty, temperance, and refraining from excessive consumption of rich foods. Though he recommended total abstinence from meat consumption, he was aware that ‘the Tide of Popular Opinion and Custom’ would still see people ‘gorge themselves with the Flesh of their Fellow-Animals’, and so he also offered advice on meat-eating in a moderate and healthy manner.

There was undoubtedly a commercial slant to these works. Many of Tryon’s books were relatively cheap, making them available to a wide audience. Tryon was well aware that a meat-free diet was not only healthy but inexpensive. In The Good House-wife Made a Doctor (1680), he taught what he called ‘Kitchin Physick’, the preparation of medicinal remedies attainable to any household, drawing on a tradition dating back to classical times.

Title page of Tryon’s The Good House-wife Made a Doctor (1685)

Cheap twenty-four-page pamphlets like A pocket-companion (1693), offered digests of Tryon’s original texts and included the usual material on avoiding excessive quantities of rich foods. Cold bread and milk consumed three or four times a day for six or eight months was one of the more spartan diets by which readers might ‘find great Benefit’. Sugar was to be consumed in moderation. Having salad on your bread instead of meat, butter or cheese was another healthy choice.

The constant repetition of these ideas through a large number of editions suggests that Tryon and his publishers never tired of spreading the word about health through moderation. In anticipation of those who might accuse him of repetitiveness, Tryon was unequivocal: ‘Needful Truths are never too often repeated, till they are once well learnt’. If today’s continuing discussions over the benefits of vegetarianism and veganism are indicative, then it seems Tryon’s writings are destined to stay relevant for some time to come.

His example shows how the concurrent phenomena of rising literacy and burgeoning print culture could make recipe books and their authors household names. The instructions in his recipes were cheap to carry out, while the books themselves were relatively inexpensive, and so they could reach a much wider audience than the medieval manuscript discussed above. For Tryon and his readers, cooking was not simply a means of preparing food, but an entire lifestyle and value system. His works remind us once again that recipes offered important forms of knowledge with far reaching social implications.

Potatoes, Beer and Cheese: scientific guides to eating in eighteenth-century Sweden

In eighteenth-century Sweden too, people realised that the importance of recipes went far beyond the preparations of cheap and wholesome meals. So much so that they were published in scientific journals. In the Proceedings of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences (Kongl. Svenska Vetenskapsakademiens Handlingar), we can find many examples on what to eat, food safety, and step-by-step recipes.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences was founded in 1739, with the aim of publishing scientific knowledge which would be of practical benefit for the nation. The emphasis, then, was on useful knowledge.These recipes weren’t just tasty, they were also a way of fighting the threats of food insecurity which existed within Sweden. Famines were a very real threat to the Swedish population, and so making the most of what you had was important. So what kinds of recipes did the journal publish?

Front page of the Proceedings of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences (usually known as "Vetenskapsakademiens Handlingar") for the year 1750 (volume XI).

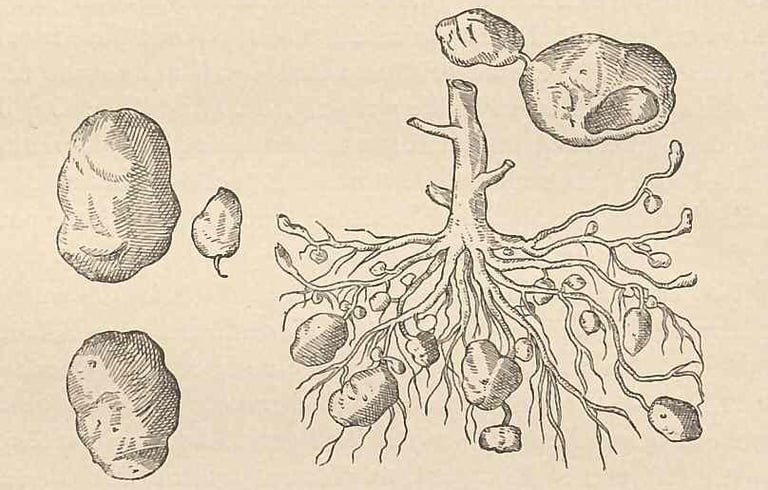

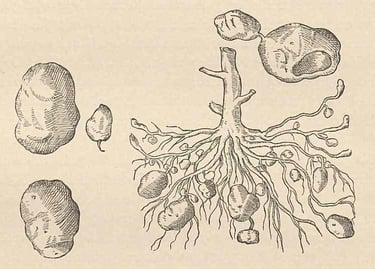

Firstly, publishing recipes was a way of introducing new kinds of food. In 1748, Eva de la Gardie (later Eva Ekeblad) published an article which described how she used a plant called ‘jordpäron’ (earth pears), or potatoes, to make bread, wine, starch and flour. The humble potato is a staple in the Swedish diet today, but in the mid-eighteenth century, it was a new (and not entirely welcome) plant.

The introduction of the potato to Sweden is often credited to Jonas Alströmer, one of the founders of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. While this was false – potatoes were grown by Olof Rudbeck the Elder at the gardens of Uppsala and were described in his 1685 Hortus Botanicus under the name peruviansk nattskatta (Peruvian nightshade) – Alströmer did play a large role in popularising the potato in Sweden. By publicising the various simple uses of potatoes through his writing in 1727 and 1732, it was hoped that the Swedish population could avoid importing foreign goods and fend off starvation.

Carolus Clusius’s botanical illustration of “Papas Peruanorum” (the Potato of the Peruvians), Rariorum plantarum historia, 1601.

Thet journal didn’t just introduce new and exotic foodstuffs, it also described how to prepare more familiar things. While the botanist Carl Linneaus was a potato sceptic (believing them to be poisonous, as they belong to the nightshade family), he had no problem sharing the secrets to making good beer. In his article Anmärkningar om Öl, (Observations on beer), he noted that it is one of the four most important drinks for mankind (the others being water, milk and wine). His description suggests that how to make beer was common knowledge, stating that ‘As every single person knows, beer is made of water, malt, hops and yeast’ , but Linneaus wanted to make sure that it was being made to the highest possible quality, so that it would satisfy even Anthimus. He noted that ‘Those who live by the sea have the best quality water, and therefore, better beer’ and that because of this, beer made in Stockholm had ‘its own unique flavour’.

He also warned of the dangers of poorly made beer. If you make it with Myrica Gale (bog-myrtle) instead of hops, it’ll give you a headache. Adding calcium, or using salt water, meanwhile, might give you scurvy. Worst of all, he referred to a sailor from London who used poor-quality yeast, which caused his stomach to explode! Recipes published in the scientific journal, then, weren’t just informative, but could save you from a gruesome end.

Finally, descriptions of how one prepared local variations of food were noted. In 1743, the society published an article on how to make cheese in Småland, an administrative district in southern Sweden. The author, credited simply as A. H. W., noted that when he travelled to the region in search of the recipes, every description of how to make the cheese was the exact same. The start of the process is much like cottage cheese; straining milk curds through a cheesecloth. Then, you must squeeze and turn it well, so that you don’t get any mold or vermin. After, that, he states that they do the following:

The cheese is placed in a cold room where no sun shines on it, otherwise it will crack. It is turned evening and morning, for the third day it is salted quite well with good fine salt, and is also always coated with pure salt, so that it does not become slimy. If the cheese is large, it is turned for one or two weeks in a fine basket but is then placed on a flat table and turned morning and evening, until it becomes quite firm.

These recipes from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences show us how recipes and scientific knowledge were connected. While the form these recipes took may have varied, from introducing new crops, to perfecting household staples and spreading knowledge of regional variations, their purpose remained the same: to gather and spread knowledge of how to keep the Swedish population nourished.

For even more interesting Swedish historical recipes, take a look at this post!