It’s impossible to be truly objective when describing the landscape. Whether intentional or not, the depiction will be shaped both by the purpose for which it is being produced, and the context that the creator is working in. This point can be demonstrated by looking at a variety of domestic Swedish travel accounts.

From the 17th century onwards, the rise of European Enlightenment brought with it an emphasis on measuring, categorising and documenting the natural world. Travel writing, both international and domestic, became an important way for people to process the world around them.

This was certainly the case in Sweden, a sparsely populated country with many regions considered under-explored by scholars and the state alike. This was especially pronounced in the case of Sápmi, the northern part of Fenno-scandia (formerly known in English as Lappland) and the homeland of the indigenous Sámi people. The Swedish colonisation of these territories was enabled with scientific travel expeditions led by explorers such as Olof Rudbeck the Younger and Carl Linnaeus.

But natural scientists were not the only ones who turned to travel writing as a means for understanding the landscape, and for spreading this knowledge to others. Let’s take a closer look at three different examples of early modern travel accounts.

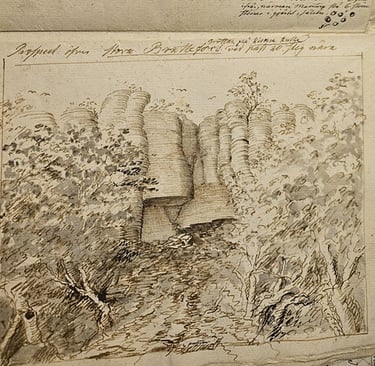

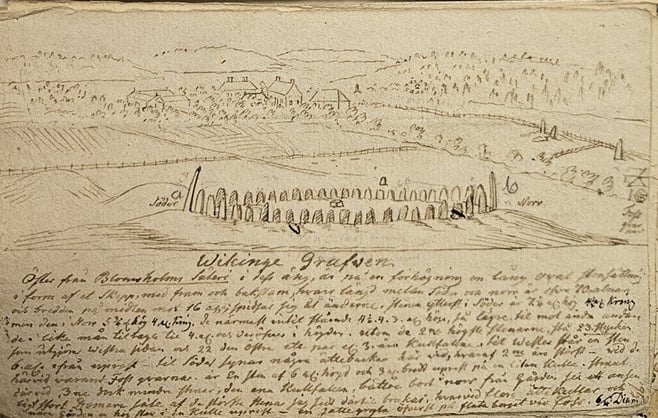

Landscape sketch by Carl Gustav Gottfried Hilfeling, 1788 or 1790.

A local travel diary in northern Sweden

Fale Abrahamson Burnam (1758-1809), a historian and high school teacher from Undersåkers socken in Jämtland in Sápmi), spent five summers between 1793 to 1802 travelling throughout his local region. Hoping to eventually publish a comprehensive book on the history, geology, archaeology, topography and economic prospects of Jämtland, he took detailed notes during his journeys.

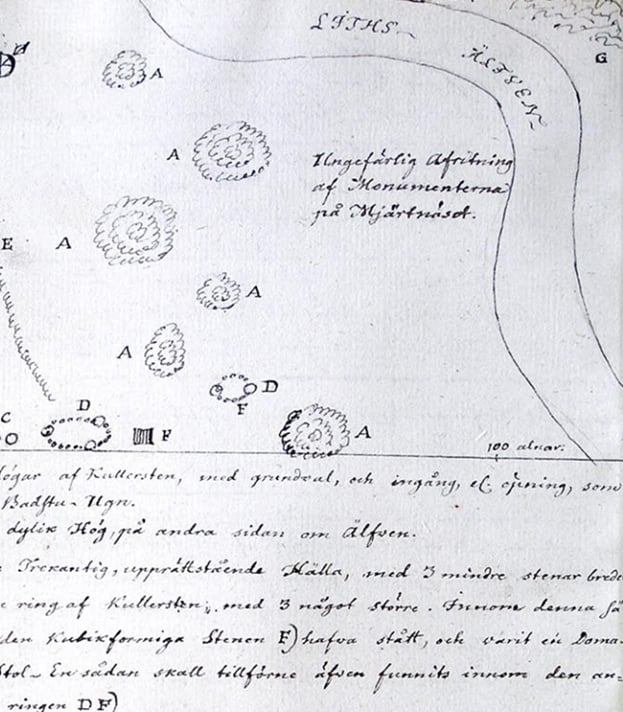

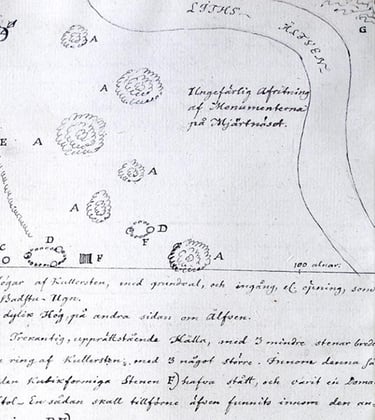

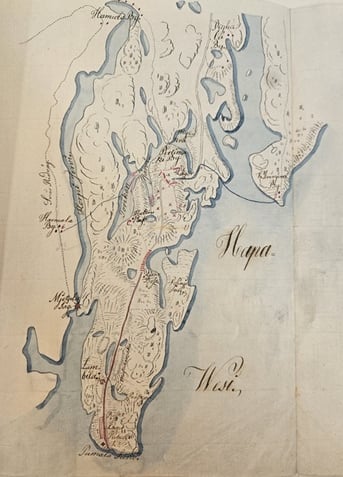

Topographical depiction of Jämtland by Fale Burnam, 1798.

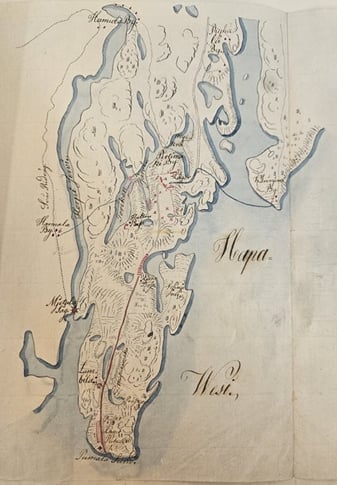

Map showing Russia’s attack on Pirtmäki camp in Finland, by Barthold Anders Ennes, 1790.

Ennes served as an officer in the Swedish army in Gustav III’s Russian wars of 1788-1790, and the Pomeranian war 1806-1808. His maps of Skåne in Southern Sweden, Finland (which until 1809 was Eastern Sweden) and Russian enemy camps were shaped by the practical needs of warfare. Instead of highlighting mineral resources or describing the local flora, the emphasis was instead on strategic vantage points, locating supply lines and rendering the terrain in ways useful to military planning. What was irrelevant to decision-making was often omitted entirely.

Antiquarian travel accounts to southern Sweden

Not all representations of the landscape focused on topography and nature. Antiquarian travel writing, produced by scholars and hobbyists seeking out historical sites, was concerned with the imprints humans had left on the land. Viking artefacts, in particular, became a major point of fascination for many of these writers, and we discussed some of these here.

Ennes himself was one such hobbyist. After retiring from military service, in addition to writing multiple books of military history which remain important for Swedish historians, he travelled across southern Sweden, documenting runestones, Viking graves, and other ruins.

Drawing of Viking grave in Blomholm by Hilfeling, 1788 or 1790.